The Bābī-Bahā’ī transcendence of khatam al-nabiyyīn (Qur’ān 33:40) as the `finality of prophethood’. [1]

Dr. Stephen N. Lambden, UC Merced.

BETA VERSION - IN PROGRESS (BELOW) - Last updated, 20-05-2018.

The downloadable Pdf version overleaf (downloadable on the main Islamo-Biblica webpage and the BBS or Babi-Baha'i Studies webpage) contains a much more recent recension and an updated and corrected version of this ongoing monograph.

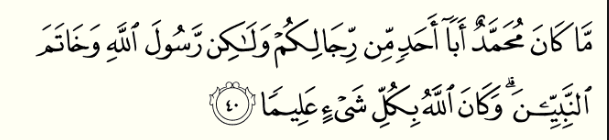

Muhammad is not the father of any man among you but he is the rasūl-Allāh (Messenger of God) and the khatām al-nabbiyyīn, the `seal’ (`last’. `best’ `acme’) of the prophets (Qur’ān 33: 40).

Lost indeed are they that cried lies to the encounter with God (liqā’-Allāh) so that when the [escatological] Hour comes to them suddenly they shall say, 'Alas for us, that we neglected it!’ (Qur’ān 6: 31).

Then We gave Moses the Book, complete for him who does good, and distinguishing every thing, and as a guidance and a mercy; haply they would believe in encounter (liqā’) with their Lord (rabb) (Qur’ān 6:155).

Whoso looks to encounter God (liqā’-Allāh), God's term (ajal) is assuredly coming (Qur’ān 29: 5). [2]

[1] This paper is a slightly modified and expanded version of a few pages of my unpublished, early 1980s / 2002, University of Newcastle upon Tyne (UK) doctoral thesis (see bib. below). An English language, occasionally further updated and expanded version of these notes, can be found on my UC Merced personal `Hurqalya Pulications’ website (see bib. below).

[2] Most of the translations of verses of the Qur’ān cited here are those of A. J. Arberry (d. Cambridge, 1969) with occasional modifications and/or added transliteration. He often translated liqā’ as “encounter”.

Khatamiyya (Q. 33:40) and Liqa' Allah (The Encounter with God).

This paper consists of interrelated notes upon the Bābī-Bahā’ī theological transcendence of khātamiyya or the khātam al-nabiyyīn (loosely, “seal of the prophets”, Qur’ān 33:40) when understood as the `finality of prophethood’. It also surveys select qur’ānic texts about a predicted future or eschatological “Encounter with God” (liqā’ Allāh) understood as an elevated messianic theophany. Often understanding the khātam in Qur’ān 33:40 to mean "last", most Muslims came to consider this verse as foundational for the post-qur’ānic doctrine of the `finality of prophethood`; that no nabī (prophet) or rasūl/mursal (sent mesenger) would appear after Muhammad, the final rasūl Allāh (messenger of God).

Perhaps echoing earlier claims of Manī (d. c. 277), the son of a Parthian prince and messianic claimant, [3] the probably Aramaic qur’ānic Arabic loanword khātam came, throughout most of the Muslim world, to indicate that the succession of pre-Islamic prophets was "sealed up" or "ended" in Muhammad just as it had previously been in Manī and in other pre-Islamic notables or claimants to prophethood. [4]It was thought that after Muhammad, sometimes even after the eschatological consummation, no future prophet would appear to found a new or renewed religion. Many commentators on Q. 33:40 have it that the Islamic belief in the second coming of Jesus indicates his reappearance as a nabī (a prophet and not a Divine figure) but in a role subservient to Muhammad and Islamic law on the Day of resurrection (Zamaksharī, al-Kashshāf, III: 544-5).

[3] al-Bīrūnī, Sachau, 1879:190; Widengren, 1955: 12f’; Ort, L. 1967:123ff; Stroumsa, 1986; Reeves, 1996: 11, 25 fns. 52-4.

[4] Note also the use of `seal of the prophets’ in pre-Islamic Samaritan sacred writings such as the 4th cent. CE., Memar Marqeh (`The Teahing of Marqeh`) where Moses is referred to as the M-Ḥ-T-M N-V-Y-Y-H (“The seal of the prophets”). See also MacDonald: 1963; text vol. I sect. V. 3, 35, p.123; trans. vol. II sect. V. 2-3 p. 201; Meeks, 1967: 221, 287 cf. p. 281-2; Stroumsa, 1976). Carsten Colpe in a 1980s article (see bib. below) has traced the `seal of the prophets’ title back to Jesus as registered by the Latin Christian author Tertullian of Carthage (d. c.. 220) via an exegesis of Daniel 9:24 contained in his Adversus Judaeos (‘Treatise Against the Jews’, c. 197 CE). Helmut Bobzin has similarly noted that the Syrian Christian theologian Aphraates (d, after 345) in his Homilies also applies the `seal of the prophets’ title to Jesus (Bobzin, in Neuwirth, 2011, p, 566 and fn.4).

The alleged `finality of prophethood’ (khatm al-nubuwwa) after Muhammad became a firmly accepted Islamic dogma. One of the traditionally 313 (or more) `sent Messengers’ (al-rasūl / mursal), the Arabian prophet is said to have completed the chain of numerous, (traditionally 124,000 or more) pre-Christian (BCE) Israelite prophets.[5] Muhammad was the “last-termination-finality" of the never to be succeeded prophets up until the Day of Resurrection. Such was variously affirmed in thousands of Sunnī and Shī`ī traditions or ḥadīth sources, as well as in numerous expository and secondary post-qur'anic literatures (see al-Ṭabarī, Tafsīr on Q, 33:40).

Even though it is not at all clear that the absolute finality of prophethood was the original intention of Q. 33:40, this finality is today something firmly entrenched in both Sunnī and Shī`ī orthodoxy (Friedmann, 1986; 1989: 49ff, 64). Any hint of another post-Islamic prophetic claim or a challenge to the i`jāz al-Qur’ān (the inimitability of the Qur’ān) has generally met with dire consequences, including theological castigation, the accusation of heresy, imprisonment, exile or execution. [6] It is yet, indisputably the case, as several respected academics and others have maintained in the light of early Islamic traditions and philological commentary and analysis, that the post-qur’ānic Islamic doctrine of the `finality of prophethood’ was not originally so clearly implied in Q. 33:40. For some early champions of emergent Islam, as well as modern academics, prophethood need not have terminated or be seen to have ended for all time with the prophet Muhammad (refer, Goldziher, Muslim Studies vol. 2:103-4; Friedmann, 1989: 58ff, 70ff; Cecep Lukman Yasin, 2010:131ff).

[5] On occasion Islamic tradition reckoned Moses the first of the “prophets of the children of Israel (anbiyā’ banī Isrā’īl), the “last” (ākhir) of them being Jesus! (so a tradition from Ibn `Abbās cited Majlisī, Bihar2 11:43; cf. 15:240’ cf. below on the Jesus related khatam speculations of Ibn al-`Arabi).

[6] As frequently noted by Ahmadiyya Muslims and other Islamic thinkers and scholars, there exists, a ḥadīth transmitted from `Ā’yisha (daughter of Abū Bakr and wife of the Prophet Muhammad), to the effect that Muslims should proclaim that Muhammad was the khātam al-anbiyā’ (= khātam al-nabiyyīn) but not state that he is the `last of the prophets’ or “one after whom there would be no prophet” (Ar. lā nabīyy ba`dahu). This ḥadīth is cited by Ibn Qutayba (d. 276/889) in his Ta’wil mukhtalaf al-ḥadīth… and by the polymathic Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī (d.905/1506) in his al-Durr al-manthūr fī’l-tafsīr bi’l-ma`thūr, vol. 5: 204 (refs, noted by Friedmann ,1989 : 63 + fn. 56 and 57).

The khatm / khātam al-nabiyyīn motif in Sufism, Islamic mysticism and twelver Shi`I Imamology and gnosis.

The Sufi and twelver Shī`ī positions regarding pre-Islamic and post Muhammad divine guidance is more complicated with their rich prophetological and diverse eschatological materials. [1] They not infrequently register future messianic-type roles occupied by Muhammad, Jesus, and the twelver Imams; most notably Imam `Alī ibn Abi Ṭālib (d. 40/661), Imam Ḥusayn ibn `Alī (d. 61/680), the Mahdi (Rightly guided one) or the twelfth Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi, known as the Qā’im (messianic “Ariser”). The “seal of the prophets” stamp is hardly rigidly applicable throughout the millennium and more of Shī`ī history with its evolving prophetology, imamology and eschatology. Its Imams are pictured as having a universal, pre-existent, and future role transcending nubuwwa (prophethood) and often centered on the related walāya (providential overseership, intimacy, friendship) phenomenon. [2] As exalted vehicles of divine guidance they, along with the Prophet Muhammad, are accorded an all-enduring role. Twelver Shī`ī traditions have it that during eschatological times, there is to be a multiplicity of prophet related and imamological “returns” or second comings. Future divine guidance mediated by a cascade of exalted individuals is anticipated in hundreds of sacred, messianic traditions relayed through the prophet Muhammad, the twelver Imams, and many others.

[1] I shall frequently use the word eschatology here in the sense of having to do with the ‘last times’ as this future apocalyptic era is detailed in numerous Abrahamic and related sacred writings

[2] The Qur’ān rooted Arabic walāya (or the synonymous wilāya) and the related walī (plural, awliyā’ = `friend, saint, overseer, leader, authority, guardian’, etc), is often indicative of an aspect of spiritual or divine intimacy, of divine providence and its human locus or vehicle of expression. Walāya has thus (among many other things) been regarded as an expression of special intimacy, friendship, saintliness, providence and overseership, etc. The human walī, for example, may be a special intimate, Saint, Friend or Sage, etc. From the early Islamic centuries, Walī became a significant human centered technical term within select Sufi circles. So too in the writings of those who sought to clarify dimensions of Shī`ī imamology. The figure of the Walī is sometimes descriptive of a human authority figure; one possessed of a role and fuction seen in the Ithnā `asharī (twelver) Imam as religious leader and authority. For Bahā’īs the Walī / Valī is the title of the `Guardian of the Cause of God’ (Persian, valī-yi amr Allāh). For some details pertinent to the many Islamic meanings of walāya, walī and the often related nubuwwa (prophethood) see Landolt, `Walayah’ in Enc.Rel. ; Radtke, 1996; Renard, 2008, especially pp. 260-263; Kamada, 455ff in Lawson, ed., 2005; McGregor, 2013, `Friends of God’ in EI3 (Brill online version first posted 2013).

al-Ḥakīm al-Tirmidhī (b. Tirmidh, near Balkh c. 204/820 - d. 320/932).

A profound theological and hagiographical mysticism surrounding the “seal” (khatm, khatam, khātim) motif in Islamic thought, theology and mysticism, can to some degree, be traced back to Muhammad ibn ʻAlī al-Ḥakīm al-Tirmidhī (d. 320/932). He was a famous Sunni ḥadīth scholar and jurist, who was to some degree subject to Shi`i influence and to the tradition of esoteric gnosis. The great Ibn al-`Arabi and numerous of his disciples, as well as many other Islamic mystical philosophers and theologians, were influenced by al-Tirmidhī‘s ideas about nubuwwa (prophethood), the khātam al-nubuwwa (the seal of prophethood), and the related notions of khatm al-walāya (the Seal of Friendship / Sainthood). His novel and important ideas surrounding the khātim al-waläya /awliya' (seal of friendship/sainthood) had a profound influence, especially as set forth in his Sirat al-awliyā' (Life of the Friends of God/ Chosen Ones/ Saints) which is also known as the Khatm al-wilāya (The Seal of the Sainthood) and the Khatm al-awliya' (The Seal of Friends of God). For him the prophetological implications, hagiographical ramifications, and deep senses of the motif of the "seal", the "seal of the prophets" and of the hierarchy of the chosen friends or "saints" crowned by their supreme leader, was of paramount significance.

In several of his many influential writings, this great Sufi theologian spoke about an elevated `Seal of the Saints’ (or Friends). He even explicitly stated in his Khatm al-awliyā' (also known as the Sirat al-awliyā', `The Seal of the Friends’ or `Life of the Friends of God'), that there exists a great leader or chief in possession of the "seal of sainthood (friendship, intimacy) with God" (khātim al-walāya). Responding to a question about the Qurān-rooted expression khātam al-nubuwwa (`Seal of prophethood, cf. Q. 33:40b), al-Tirmidhī wrote:

[58] For the “Seal of prophethood” (khātam al-nubuwwa) is an origin and a nature (bada’ sha`n) which is wondrous (`ajīb) and profound (`amīq), more profound (a`maq) than you can possibly conceive … [61] God gathered together in Muhammad all the parts of prophethood (ajzā’ al-nubuwwa) and having thus perfected prophethood, He set His seal upon it (bi-khatmi-hi). And because of that seal (al-khatm) neither Muhammad's carnal soul, nor his enemy [Satan], found the means to penetrate the place of prophethood [within him]”. [1]

[1] Sirat al-awliyā', ed. Radtke 1992 sect. 58 p. 40; sect 61 p. 41; trans. Lambden + O'Kane, 1996, 104, 106. cf. al-Tirmidhi, Khatm al-awliyā, ed. Yahya, 161f

The focus of al-Tirmidhi’s hagiography was not upon any limited notion of the finality of prophethood or sainthood. In his elevated concepts surrounding the “seal”, he made room for a future hierarchy of Sufi saints, mystics and sages. As cosmic powers, certain among them (such as the later 40 or 356 abdal or “substitutes”) were viewed as very elevated persons. Sometimes their leader (s) took on a messianic type persona, were subject to divine inspiration, and were thought to have a very important role in eschatological times. al-Tirmidhī even speaks of a special, chosen walī (Intimate of God, Friend of God, Saint) who will come forth on the Day of Judgement and be in perfect or complete possession of the khātim al-walāya, the “seal of Friendship with God”:

Whenever one of them dies, another follows after him and occupies his station (maqām), and it will continue until their numbcr is exbausted and the time comes for the world to end. Then God will send a Friend (walī) whom He has chosen and elected, whom He has drawn unto Him and made c/ose, and He will bestow on him everything He bestowed upon the [otber] Friends (al-awliyā’) but He will distinguish him with the seal of Friendship with God (bi-khatim al-walāya). And he will be the Proof of God (Ḥujjat Allāh) on the Day of Resurrection (yawm al-qiyāna) above [against] all of the other Friends of God (awliyā’). By means of this seal he will possess the sincerity of Friendship with God (ṣidq al-walāya) the same way that Muhammad possessed the sincerity of prophethood (ṣidq al-nubuwwa). [1] = Sīrat al-awliwā’, 64, ed. Radtke 1992, sect. 64 pp. 44-5, trans, O'Kane, 109f adapted Lambden.

This special figure, distinguished in the Sirat al-awliyā’ as the khātim al-walāya (“seal of Intimate Friendship with God”; sect 64.), was later referred to by some as the al-ghawth ("the Helper, One who assists") and al-quṭb (“the Pole, Apex”). He is the supreme eschatological Ḥujjat Allāh (the “Proof of God”) and one especially intimate with God as the walī Allāh. This title Ḥujjat Allāh was sometimes applied to the expected Shī`ī messianic twelfth Imam and was often utilized by the Bāb himself in his Qayyūm al-asmā’ and many other writings. [1]

Muhyi al-Din Ibn al-`Arabi (d. 638/1240).

The influential master of Islamic mysticism, Ibn al-`Arabī (d. 638/1240) with numerous of his commentators, made much of the concepts of nubuwwa (prophethood) and wilāya, loosely, human mediated providential guidance from such as are intimate with God. For the Great Shaykh, walāya is essentially the bāṭin (inner depth) of nubuwwa, itself of various kinds. The following (loosely translated) passages from the al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya (The Meccan Disclosures) revolve around khātam (seal) concepts touching upon modes of nubuwwa (prophethood) and of wilāya (provindetial guidance), and must suffice to illustrate these developments:

Walāya (divine guidance) is expressive of nubuwwa `āmma (general prophethood) and that prophethood which is legalistic (al-tashrī`) also known as nubuwwa khāṣṣa (specific prophethood)... Muhammad is the khātam al-nubuwwa (seal of prophethood) for there is no prophethood (nubuwwa) after him. Yet after him was the like of Jesus among the ūlū al-`azm (those characterized by steadfastness) of the Messengers (al-rusul) and certain specified Prophets (al-anbiyā’)... [in due course] there will be disclosed a Walī ("Chosen Intimate’, `Saintly Leader") possessed of absolute prophethood (nubuwwa al-muṭlaqa)... (Futuhat, II: 24ff, 47ff; cf. I: 200, 429; Fusus,134-6; 160, 191).

This special figure, distinguished in the Sirat al-awliyā’ as the khātim al-walāya (“seal of Intimate Friendship with God”; sect 64.), was later referred to by some as al-ghawth ("the Helper, One who assists") and al-quṭb (“the Pole, Apex”). He is the supreme eschatological Ḥujjat Allāh (the “Proof of God”) and one especially intimate with God as the walī Allāh. This title Ḥujjat Allāh was sometimes applied to the expected Shī`ī messianic twelfth Imam and was often utilized by the Bāb himself in his Qayyūm al-asmā’ and many other writings. [1]

[1] Ibid., and see further Abrahamov, 2014, 85-90; Elmore 1999, 2001, index, .

Maḥmūd ibn ʻAbd al-Karīm Shabistarī (b. Shahbistar [near Tabriz] c. 686/1287 - d. c. 720/1320).

Sufi insights surrounding the khātam al-nabiyyīn and associated matters touching upon finality and non-finality, cannot be comprehensively dealt with here. The following stanzas from the Persian Gulshan-i rāz (The Rose Garden of the Secrets) of the Ibn al-`Arabī influenced Maḥmūd ibn ʻAbd al-Karīm Shabistarī (d. 740/1340), must suffice to give an indication of deeply profound khātam (“seal”) related insights. They provide a glimpse into the fascinating universe of the mystical and messianic dimensions of doctrines inspired by the qur’ānic khātam (”seal”) motif:

Prophethood (nubuwwat) came to be manifest in Adam, Its perfection (kamāl) was realized through the existence of the Khātam [Muhammad].

Wilāyat (“Intimate guidance”) lingers behind while it makes a journey,

As a [Prophetological] Point (nuqṭa) in the world, it scribes another cycle.

Its theophany in its fullness (ẓuhūr-i kull-i ū) [through Him] will [erelong] be realized through the Khātam (`Seal’)’.

For through him the cycle of Existence (`ālam-i wujūd) will be completed.

His chosen ones (awliyā’) are even as his bodily organs (`aḍw).

While he Himself is the Pleroma (kull), they constitute segments thereof.

As one intimate with the Master (khwajah), his Providence complete,

Through him will Universal Mercy (raḥmat-i `āmm) find realization.

An Exemplar he shall be throughout both worlds, a Leader (khalīfa) for the progeny of Adam (Gulshan, 1978 : Per. 369-374 pp. 22-3, trans.Lambden), [8]

In summary, as I understand these lines: The first man Adam initiated primordial prophethood (nubuwwa) which came to be perfectly fulfilled or realized in Muhammad, its “seal” (khātam). The potent, supra-prophetological force of walāya (“Guidance”) as a “Point” or locus of Divine Reality, came to express itself through scribing, writing out, initiating or delineating, a new cycle or era. As a result the fullness of a Divine Theophany related to the Khātam (Seal) will come about. Through this evolution, by means of a future Exemplar and Leader, Universal Mercy (raḥmat-i `āmm) will find realization. Transcending finality, the “Seal” through its transcendent walāya (divine potentiality) becomes a future locus of universal, Divine Guidance.

Some commentators on Ibn al-`Arabī and his many writings, reckon that he himself was or claimed to be the khātam al-walāya (the Seal of Divine Intimacy). Many of his disciples certainly saw him in this light.

[8] On Sufi aspects of the khātam al-nabiyyīn in Ibn al-`Arabī etc see further al-Futuhat and the Fusis al-Hikam (indexes) as well as Friedmann, 1989: 71ff + index.

The Commentary of Muhammad ibn Yaḥyá al-Lahījī on the Gulshan-i rāz (The Rose Garden of Secrets).

Twelver Shī`ī Imamology, Prophethood and the Walāya phenomenon.

Ḥaydar al-Āmulī (b. Āmul 719–787 / 1319–1385).

This learned twelver Shī`ī scholar and mystic was much influenced by Ibn al`Arabī upon whose seminal Fuṣūṣ al-ḥikam (The Bezels of Wisdom) he wrote a commentary entitled Naṣṣ al-nuṣūṣ (The Provision of Provisions). His position of the matters of interest here have been well summed up by Kohlberg in his Encyclopedia Iranica article on al- Āmulī

In accordance with Āmolī’s system, the Mahdī must be a walī, not a prophet; indeed, Āmolī follows Saʿd-al-dīn Ḥammūya (d. 650/1252) (in his al-Maḥbūb) and ʿAbd-al-Razzāq Kāšānī (d. 730/1330) in maintaining that the seal of the universal (moṭlaq) walāya is ʿAlī and the seal of the particular (moqayyad, Mohammadan walāya is the Mahdī (who for Āmolī is identical with the Twelfth Imam). On this issue Āmolī differs from Ebn al-ʿArabī, who identified the ḵātam al-walāyat al-moṭlaqa with Jesus and who was himself regarded by some of his disciples as the ḵātam al-walāyat al-moqayyada (Jāmeʿ al-asrār, pp. 385, 395-448). (Kohlberg EIr. Vol. 1: 983-985).

Muhammad Muhsin Fayḍ al-Kashānī (d. Isfahan 1091/1680),

Add here ...

In many Sufi circles and within streams of Twelver Shī`ism, the personified walāya expressed through the walī as Friend, Saint, Intimate or messianic Imam, all but exploded the constraints of the finality of the prophetological tradition. For some the Islamic universe came to embrace or expect a future supreme walī, Guide-Mahdī or `Perfect Human’ (al-insān al-kāmil). For many deep thinkers the finality of providential divine guidance failed to be utterly finalized.

The Islamic Vision of the “Lord” (al-rabb) on the Day of Resurrection.

“God is He who raised up the heavens without pillars you can see, then He sat Himself upon the Throne... He distinguishes the signs; haply you will have faith in the encounter with your Lord (liqā’ rabbika)” (Qur’ān 13: 2).

“No indeed! When the earth is ground to powder, and thy Lord comes forth (wa jā` rabbuka ), and the angels rank on rank” (Qur’ān 89: 21-22).

“Faces [of believers] shall shine brightly (nāḍira) on that Day [of Resurrection] gazing upon their Lord (rabb)” (Qur’ān 75: 22-3).

The Islamic implications of such qur’ānic verses as have been cited above, have been well summed up in the following succinct manner by Murata and Chittick:

“We have seen that the Koran promises in no uncertain terms that people will encounter their Lord. One of the questions that theologians often debated was whether or not this encounter implied the vision of God. Most thought that it did, and they had Koranic verses and hadiths to support them. The general picture, in fact, is that the vision of God is the greatest possible bliss, and that all those taken to paradise will achieve it. However, those who remain in hell will be barred from this vision, and this will amount to the worst possible chastisement” (Murata and Chittick, 1994: 177).

In line with those Qur’ānic passages which speak of the eschatological therophany, the encounter or meeting (liqā’) with the Lord (rabb) (see Q. 13:2) and of the eschatological vision of the Lord (rabb), there are traditions ascribed to Muhammad about a latter-day vision of God as the resplendent and luminous “Lord” (rabb). [1] One such frequently recorded Sunnī tradition, is registered in slightly variant forms in the Ṣaḥīḥ (the Reliable/Sound) of Muhammad ibn Ismā’īl al-Bukhharī (d.256/870), Within, for example, the Kitāb al-Tafsīr (Book of Qur’ān Commentary) the following tradition narrated from Abū Sa'īd aI-Khudrī (c/ 65/584) is found:

During the lifetime of the Prophet [Muhammad] it was said, `O Messenger of God! Shall we see our Lord (rabb) on the Day of Resurrection (yawm al-qiyāma)?’ The Prophet said, `Yes!’ (na`am); do you have any difficulty in seeing the sun (al-shams) at midday when it is bright (ḍaw’) and there is no cloud (al-saḥāb) [in the sky]?" They replied, "No." He said, "Do you have any difficulty in seeing the moon (al-qamar) on the night of the full moon (laylat al-badr) when it is bright (ḍaw’) and there is no cloud (al-saḥāb) [in the sky]?" They replied, "No." The Prophet said, Likewise will you have no difficulty in seeing God (Allāh) on the Day of Resurrection as you have no difficulty in seeing either of them [the sun or the moon]… (Lambden, trans. Arabic Bukharī, 1997, al-Sahih, vol. 6, Bk. 65 No. 4581, pp. 90-92).

This above ḥadīth from the Ṣaḥīḥ of al-Bukharī, further has it that “On the Day of Resurrection … the Lord of the worlds (rabb al-`ālamīn)” will come to various ummat (religious communities)” in a “form”, “shape” or mode closest (adnā sūrat) to the vision of Him expected or “generated by the people themselves”. It then adds that the true eschatological vision of God will be a universal, personal vision of the Qur’ānic God.

Several Sunnī traditions about the vision of the Lord on the Day of Resurrection are also found in the Kitāb al-Tawḥīd (Book of the Divine Unity) within the Ṣaḥīḥ of al-Bukhharī where they are considered expository of Qur’ān 75:22-23 (cited above), including the following narration from a certain Jarīr ibn 'Abd-Allāh al-Bajalī (d. ca. 51/671),

We were sitting with the Prophet [Muhammad] and he looked at the moon (al-qamar) on the night of the full moon (laylat al-badr) and said, "You shall see your Lord (rabb) just as you see this [full] moon (al-qamar), and you will have no difficulty or trouble in observing Him (ru’yatihi)… (Lambden, trans Arabic Bukharī, 1997, al-Sahih, vol.9, Bk. 97 No. 7434. p. 318).

More categorically, Jarīr ibn `Abd-Allāh al-Bajalī is again cited by al-Bukharī as narrating that the Prophet said:

"You will indeed see your Lord (rabb) with your own eyes" (satrūna rabbakum `iyyān an) (Lambden, trans Arabic Bukharī, 1997, al-Sahih, vol. 9, Bk. 97 No. 7435. p. 318), [2]

In certain of these and other early, related traditions, the expected normally formless Lord (rabb) is to appear on the Day of Resurrection in human-like (“anthropomorphic”) “form’ (ṣūrat). In some texts this has messianic and theophan- ological implications. Within Islamic theological writings, it is admitted that God may manifest Himself in whatever manner he pleases; as, for example, a human-like Deity (human beings are in “His image” Gen. 1:27) redolent of divine, supernatural beauty (al-jamāl). In some traditions God, the latter-day Lord, is pictured as taking on beautiful bodily forms, like that of the youthful prophet Jesus or Muhammad. Even the archangel Gabriel is said to have assumed the stunningly beautiful form of the merchant Diḥya al-Kalbī (d. c. 45/618; see Lammens and Pellat, “Diḥya”, in EI2 ). According to Islamic sources, God, the Lord, may thus exhibit outstandly beautiful features, appearing at timesr as an adolescent “beardless youth” (al-shābb / amrad) [3] or as an “Ancient of Days old man or Shaykh. According to Anas ibn Mālik (d. 91-93 /708-10), Muhammad himself is said to have stated,

I saw my Lord (rabbi) in the most beautiful form (aḥsan sūrat) like a youth with abundant hair (ka'l-shābb al-mūfìri) on the throne of grace (kursī karāmat), with a golden rug (firāshun min dhahab) spread out around Him… (cited Ritter 2003: 459). [4]

Bābī and Bahā’ī sacred writings often underline the fact that God can never be directly seen or incarnated as a human being (Q. 6:103, Q. 112). Yet, He can be visioned or “seen” after the “image” of his divine Manifestation who is often pictured in human, super-human or in diverse symbolic and supernatural terms. Without incarnation, the formless, yet imaged divine “Beauty” according to Abrahamic religious sources, suffuses the whole of creation and may be visioned. Bahā’-Allāh and his successors taught that past prophets visioned the eschatological Lord as the human-like “Glory” (kavod) or the divine Splendour of God (see Ezekiel 1:26f and 10; Revelation 1:12ff), as an archangelic being such as Michael (Heb. = “One like unto God”), or as the Danielic “Ancient of Days” (Dan. 7 : 7, 9, 22; 1 Enoch 46:1; 71:10). The symbolic language of Abrahamic sacred scripture and numerous post-biblical Jewish writings, have the great Messenger founders and expected manifestation of Divinity, as being portrayed in elevated human and/or Divine terms. Though never to be taken literally, the sacred writings of the world’s religions, including Islamic ḥadīth texts, somethimes picture God in elevated “human” terms. Eschatological portraits of Divinity with messianic implications are sometimes viewed by Bahā’īs as glimpses of the “Glory-Beauty” (Bahā’) of the person of Bahā’-Allāh. The eschatological `coming of God’, the Lord, is demythologized in Bābī-Bahā’ī texts relative to messianic, prophetic fulfilment (see further below).

[1] There exist many ḥadīth about the eschatological vision of God, the resplendent Lord, in numerous respected Sunnī and Shī`ī Islamic sources. These include numerous Islamic Tafsīr literatures and, for example, the ḥadīth collections of al-Bukhārī, Muslim (d. 875 CE), Ibn Mājah (d. 886 CE), al-Tirmidhī (d. 815 CE), Abū Dāwūd (d. 888 CE) and al-Nasā’ī (d. 915 CE), as well as in the early al-Muwaṭṭā’ (“The Approved”) of Imam Mālik ibn Anas (d.179/795).

[2] Refer further to the similar traditions about the vision of the Lord on the Day of Resurrection recorded by al-Bukharī in the Kitāb al-Tawḥīd (Book of the Divine Unity), from Jarīr (No. 7436, pp. 318-9), from 'Ata' ibn Yazid al-Laithi as narrated from Abū Hurayrah (No. 7437, p. 319-322), from 'Aṭā' bin Yazid several times from Abū Sa'īid al-Khudrī (No. 7438, p. 322+ No. 7438, p. 322), etc

[3] The prophetic tradition relayed from `Ikrima picturing the “Lord” as a “beardless Youth” (al-shābb) can be found in various hadith collections and in numerous Sufi and other sources including the writings of the great mystic Ibn al-`Arabī (d. 1240). See his al-Futuḥāt al-makkiyya (“The Meccan Disclosures “) vol. I: 97, 755; II: 377, 426; III: 111, 330, IV: 182, 474 etc. For further details and references in early Islamic literatures, Ritter, 2003 esp. Ch. 26 p. 460f.

[4] Traditions relayed from Ibn `Abbas (d. c. 68/687), the `Father of Tafsir’, have it that on the night of his Mi`rāj (ascent through the heavens), Muhammad saw Jesus as a snow-white (bayḍā’) shābb (youth) with curly or long hair. Also worth noting here are the observations of the 8th Imam `Alī al-Ridā’ (d. 201/818), on a possibly originally Sunnī registered tradition (summed up by Hisham ibn Salim, Salīḥ al-Taqi and al-Maythamī) about an alleged vision of Muhammad picturing God a as a youth of thirty years but `hollow’ down to the navel) then of solid form, apparently for standing upright (see al-Kulaynī, al-Kafi, Pt. II. Sect. 10, Hadīth 266).

The Eschatological Encounter / Meeting with God, the Lord.. [1]

Great messianic, theophanological importance was given by the Bāb and Bahā’u’llāh to the qur’ānic references to liqā’- Allāh, the latter day meeting or encounter with God (including Q. 6:31; 130, 154; 7:51,147; 10:7ff; 13:2 etc.). [2] In the Qur’ān itself the eschatological Day of Judgement or Resurrection (yawm al-qiyāma), is referred to as the yawm al-talāqi, the “Day of the the Encounter” with God (see Q. 40:55). This future era of the interface, beatific vision or meeting with the Divine is referred to around twenty-four times in thirteen different surahs (chapters) of the Qur’ān (see above and Kassis, Concordance, 744). In the Bābī-Bahā’ī viewpoint, the Qur’ānic liqā’-Allāh is not simply an individual post-death or afterlife beautific experience, but an individual and/or collective end-time experience of God through his latest Messenger, the eschatological Manifestation of God who represents the Godhead in the worlds of creation.

[1] For a complete list of references for the qur’ānic liqā’ Allāh, including nominal and verbal uses of the root letters (l-q-w) see Kassis, Concordance, 744f.

[2] While numerous other translations are possible, the centrally important qur’ānic Arabic phrase liqā’ Allah will usually be translated here with the suitably neutral “encounter” / “the encounter with God” (so Arberry). Among possibilities, the translation “the meeting with God/ the Lord” is especially appropriate to its Bābī-Bahā’ī historical and theological senses.

The Persian and Arabic Bayāns (Expositions).

Though present in earlier writings dating prior to 1848 (after 1260 AH/1844 CE), the Bāb gave clear elucidation to the meaning of the Qur’ānic promise of the liqā’ Allāh (the Encounter / Meeting with God) in his Persian and Arabic Bayāns or scriptural `Expositions’ set down around 1848. The encounter or meeting with God/ the Lord is the specific subject of Bayāns III.7 (cf. II.7; VI.13 VIII.5). In the Persian Bayān, the Arabic-Persian word liqā’ encounter meeting, etc., occurs more than fifty times. Aside from God himself this key term (or other verbal and nominal forms of the Arabic) is most frequently linked with Muhammad, the Bāb and the messianic man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh (Him whom God shall make manifest). Having theophanic import, it is often associated with the Manifestation of God (maẓhar-i ilāhī) or with his many associated titles such as mashiyyat (the Divine Will) or the shajarat-i ḥaqīqa (Tree of Truth). In the writings of the Bāb references to the encounter with God are often found in theologically complex contexts. They often express sentiments summed up in the following beatitude of the Bāb found in Persian Bayān VIII.6, “Blessed be whomsoever comprehends the liqā’-Allāh (Encounter with God) on the Day of His theophany (ẓuhūr)” (printed ed., 287). [1] The following few paragraphs sum up and comment upon a select number of key references of the Bāb to the subject of the Encounter with God (liqā’ Allāh), the Lord in his Bayāns. They have to do with past divine manifestations and with a coming, realized or future eschatological theophany. [2]

[1] Note also the following beatitude in P. Bayan VIII.16, “Blessed be whomsoever maketh mention of Fatherhood (abuwiyya) relative to the Dhikr (messianic Remembrance) of His Lord!” (p. 301).

[2] See especially Persian Bayan (with page refs. from the well-known printed edition) : I.1 (p.3); II.1 (pp. 3, 19, Qur’an 13:2 is cited here); II. 7 (pp. 30-33); II. 8 (p.36); II.16 (p. 58, 63); II.17 (p. 66, 71); II.18 (p. 73); III. 3 (p.78); III. 7 (pp. 81-82, around 18 refs. in this section); III.11 (p. 90); IV. 8 (p. 128); IV.17 (p. 146); VI.13 (219-228 Qur’an 13:2 [3] is again cited or paraphrased on p, 222 here); VI. 8 (p.213); VI.13 (p.222, 226); VII. 6 (p. 247); VII.6 (p.247); VII.17 (p. 263 = tilqā’ al-shams; p. 265); VIII.1 (p. 274); VIII.2 (p. 277-8); VIII. 6 (p. 287, a Beatitude); VIII.16 (p. 301); VIII.17 (p.304); IX.3. (pp. 314, 317), etc.

Unlike its probably earlier Persian counterpart, the often terse Arabic Bayān only occasionally (less than seven times) directly refers to the liqā’-Allāh/ al-rabb.[3] Arabic Bayān II: 7 on the Day of Resurrection, makes important passing reference to the liqā’ Allāh, the Encounter with God and may be loosely translated as follows:

The seventh gate [Unity II.7] concerns the Day of Resurrection (yawm al-qiyāma) just as you have come to understand. From the onset of its dawning forth through the Sun of Glory (shams al-bahā’) until the time of its setting, is better in the Book of God than any period of “Night” (al-layl), as is evident to such as comprehend. Indeed! God did not create anything save for this Day of Resurrection, for thereon all are destined for the liqā’ Allāh, the Encounter with God, consonant that is with such action as accord with His good-pleasure.

On the Day of Resurrection this [liqā’ Allāh] will be outwardly realized (ẓāhiran) … Whosoever attains the Encounter with Him [God] (liqā’ihi) hath assuredly attained the Encounter with Me (liqā’ī) [the Bāb] though one should not be content with this if one has not had personal experience thereof. Wherefore, should thou be mindful of this quintessence of the [eschatological Day of the] Hereafter (ḥarf al-ākhir) and be conscious of thine own limitations (Ar-Bayān II: 7, text in al-Ḥasani, 84 cf. Nicolas 1905:103-4).

Here the yawm al-qiyāma (Day of resurrection) is identified by the Bāb with the “Day” of the liqā’-Allāh, the Encounter with God. It commences with the rising up of the manifestation of God as the radiant “Sun of Bahā’-Glory” which eclipses the phase or era of the “night time” of the darkness of unawareness or irreligiosity. The personalistic theological actualization of the liqā’ Allāh (encounter with God) on the `Day of Resurrection’, is the faith-generating encounter or meeting with the Bāb himself, along with the practise of such deeds as are befitting of his new era and are acceptable to God.[4]

[3] See especially Arabic Bayān (with page refs. from the well-known al-Hasani printed edition) II.7 (p, 84); III.7 (p, 86); cf. VII.9 (p.94 tilqā’); X.6 (p.101; expressed verbally; cf. Qur’ān, 43:83; 52:45; 70:42).

[4] As early as 1865, Gobineau (with the assistance of others) translated the Arabic Bayān which he entitled the `Ketab-e-Hukkam’ (sic. for the Arabic Bayān) in Les Religiones… 2nd ed. 1866, pp. 461-543. For Ar. Bayān II: 7 see p. 478. The French writer Nicholas also translated Arabic Bayān II: 7 pages 103-4 in his 1905 translation, Le Bayan Arabe… (see bib. below).

Persian Bayan II: 7 also describes itself as pertaining to the Day of Resurrection which is here defined as “the Day of the Manifestation of the “Tree of Reality (yawm-i ẓuhūr-i shajarat-i ḥaqīqat)”, something synonymous with the era of the theophany of the Messenger of God. Acting contrary to what should take place at the time of the eschatological liqā’ Allāh (Encounter with God), people exiled the Bāb from the heart of the Islamic world to a remote mountain in Ādhirbayjān (NW Persia) known as Mākū. Because God, the Most Sanctified Essence (dhāt-I aqdas), is ever beyond human approachability, people were destined to meet his representative, the Bāb as the `Tree of Reality. Meeting him as the Primordial Tree (shajarat-I awwaliyya) is the meeting with God promised in the Qur’ān. This encounter, however, in the light of his worldly occultation in Mākū, might be fulfilled by obtaining a token devotional portion of clay (ṭīn) from the vicinity of his Shiraz house (or perhaps the Meccan Ka`ba). Associated actions could then be viewed as tantamount to realizing the Encounter or Meeting with God in the face of the unavailability of the person of the Bāb (P Bayan II.7, printed ed, pp. 30-33).

Speaking with the voice of God in Arabic Bayān III: 7, the Bāb boldly opens this section by declaring that human beings, “my creation/creatures”, can never comprehend His Reality, let alone gain any direct vision of Him. It is thus the case that whatever was revealed in the Qur’ān about the liqā’ (Encounter / Meeting) with Him, forever has and will forever pertain to the one who represents Him. Knowledge of this is “Greatest of Paradises” (a`ẓam al- jannāt). This can be grasped by such as are capable of appropriating deep “gnosis” (`irfān). [2]

The Arabic summary prefixed to Persian Bayān III: 7 places the messianic successor to the Bāb, man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh (Him whom God will make manifest) at the centre of the eschatological Encounter/Meeting with God (liqā’ Allāh): [3]

The seventh gate of the third unity concerns that which God hath revealed concerning the meeting with Him (liqā’) or the meeting with the Lord (liqā’ al-rabb). This since the intention is the person of man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh (Him whom God will make manifest) for God in his Essence (dhāt) cannot possibly be seen.

The subsequent, main text of Persian Bayān III: 7, continues by underling the incomprehensibility and indescribability of the Ultimate Divine Essence (dhāt-i azal), Godhead or the Real (ḥaqq).[4] The scriptural mention of His liqā’ (the Encounter) is outwardly possible only through His Manifestation (ẓāhir bi-ẓuhūr-i ū) by which is intended the “Point of Reality” (nuqṭat-i ḥaqīqa) which “hath ever been and will forever remain the Primal Will of God (mashiyyat-i avvaliyya)”. The Qur’ān, the Bāb continues, makes mention of both the liqā’ Allāh (the Encounter with God) and the liqā’-i Rabb (Encounter with the Lord). This through the aforementioned Primal Will of God (mashiyyat-i avvaliyya) centered in the Prophet Muhammad, the Messenger of God (rasūl Allāh). In stages, or little by little, there is a further descent of this primordial Reality (centred in Muhammad) until everything (har shay’) is affected by the powers of the encounter; though, he adds, there is no obvious evidence for this, save what God himself discloses of the descending ramifications, the shadows of that Primordial Reality (ḥaqīqat-i avvaliyya). This divine phememonen is evident in the Reality (ḥaqq) of the rightly-guided twelver Imams, for “whomsoever hath known them, hath indeed known God”. The liqā’ Reality of the encounter descended in a similar manner through the knowledge or gnosis (`ilm) of the Bāb as a “Gate” (bāb-i maftūḥ) swung open. A new fullness of Divinity was made possible through the youthful Sayyid of Shiraz.

The “Pre-Existent Reality” also made possible the liqā’ Allāh (Encounter with God) relative to the Reality (ḥaqq) of the person of faith or believer (mu’min). The believing soul is able thereby to attain a state of “bliss” or “happiness” (surūr), which is described as the very bliss or happiness of Muhammad the Messenger of God, further said to be tantamount to the “bliss” or “happiness” of God Himself (surūr-i khudā). On the other hand, the believing soul may come to experience a state of “lamentation” or “sadness” (ḥuzn) which is again said to be tantamount to the “lamentation” or “sadness” (ḥuzn) of the Prophet Muhammad and thus of God Himself. The goal of the true believer is to attain to the “Primordial Divine Reality” through the persons of the Gates of imamological or eschatological guidance (ḥaqīqat-i avvaliyya-yi abwāb-i hudā). In this way every soul may attain their ultimate goal relative to the mystery of the liqā’-Allāh (the Encounter with God).

The case of the effect of these primordial liqā’-Allāh (Divine encounter) generating divine forces on the wayward unbeliever, is said to result in nothing but “hell-fire” (al-nār). The encounter with God becomes an act of eschatological judgement resulting in archetypal “happiness” (al-surūr) or deep “sadness” (al-huzn), the paradise of “heaven” or the depths of “hell”. Any person who attains to the post-Babi, messianic man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh (Him whom God will make manifest), has truly experienced the great liqā’ Allāh / liqā’-i rabb, the fullness of the Encounter with God or the Presence of the Lord. [5]

Persian and Arabic Bayāns VI.13 concern the number of the gates or entrances to the house of the Bāb; they should not exceed ninety-five (= 5 x 19). Perhaps because gateways can be openings to a place of spiritual encounter, the subject of the encounter/meeting with God (liqa’ Allāh), is several times raised. Mention is made of the duration of the Islamic dispensation (spanning 1270 years or up until 1260 AH = 1844 CE), then to a period of Ziyāra (sacred Visitation) for the purpose actualizing the “Encounter with God” (liqā’ Allāh). It is explicitly stated that “all were created” for this (p, 222). Linked with the `Encounter with God’ (liqā’ Allāh) or with the Lord, this Ziyārat (visitation) to the house of the Bāb, this matter is referenced in the key opening verse (verse 2 or 3) of the Sūrat al-Ra`d (`Surah of Thunder`, Q, 13). The Divine encounter through a sacred journey is further related to visitation to the site of the bodies or tombs of the `Letters of the Living’ (ḥurūfāt al-ḥayy ; eighteen of the Bāb’s most important disciples). Towards the end of VI.13 ( printed ed. p.226), the rising up of the Sun of Reality (shams-i ḥaqīqat) is associated with a state of preparedness for the Encounter with God (liqa’ Allāh) on the Day of Resurrection (yawm al-qiyāma) (printed Azali, ed. pp. 219-228). Finally, in this connection, it should be noted that Arabic Bayān VI.13 boldly relates the encounter with God (liqā’ Allāh) with a meeting with the Bāb himself. This is declared to be the “greatest of Paradises” (a`ẓam al-jannāt) (Ar, Bayan III.7, al-Hasani, p. 86).

[1] As early as 1865, Gobineau (with the assistance of others) translated the Arabic Bayān which he entitled the `Ketab-e-Hukkam’ (sic. for the Arabic Bayān) in Les Religiones… 2nd ed. 1866, pp. 461-543. For Ar. Bayān II: 7 see p. 478. The French writer Nicholas also translated Arabic Bayān II: 7 pages 103-4 in his 1905 translation, Le Bayan Arabe… (see bib. below).

[2] For Ar. Bayān III: 7, see Gobineau, `Ketab-e-Hukkam’ in Les Relgiones, p. 484. Nicholas also translated Arabic Bayān III: 7 on page 114 of in his 1905 translation, Le Bayan Arabe…

[3] The messianic phrase man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh (Him whom God will make manifest) was very frequently used by the Bāb in his later writings to designate his successor and/or future successors. This elevated figure is mentioned over 200 times in the Persian Bayān. For Baha’is this title was taken as a reference to Bahā’u’llāh himself (see further below).

[4] I have consulted the original texts of Persian Bayan III: 7 in Minasian Coll. Ms. 741, pp. 165-168; INBMC 24: 161-2; Azalī ed. 81-82. cf. also Nicholas 1913, II: 28-31. See further, Browne, `A Summary of the Contents of the Persian Bayān’ (on Per. Bayan III: 7) in Momen ed. 1987.

[5] A 1913 French translation by Nicolas of Per. Bayān III: 7 can found in volume 2 (pp. 28-31) of his 4 vol. translation of the Persian Bayān (see bib. below). An Azalī printed edition of the Persian Bayān was first printed in the 1960s (see bib. below).

The Persian Dalā’il-i sab`a (Seven Proofs).

The Bāb registers the theological centrality of the liqā’ Allāh (Encounter with God) in his Persian Dalā’il-i sab`a. After celebrating the exalted status of the Prophet Muhammad, he underlines the fact that all were created for the purpose of the eschatological liqā’ (Encounter/Meeting), though not for actualizing any direct relationship with God, the apophatic, Eternal Divine Essence (dhāt-i azal). Rather, it revolves around an interaction with His agent of communication, the Divine Manifestation of Reality (maẓhar-i ḥaqīqat). On this level nothing can establish the depth of His gnosis (`irfān) though this matter is known by virtue of His own Logos Self (bi-nafsihi). The rulers or kings of the Islamic domains during the Qajar period, in their wastefulness and self-centeredness, are said by the Bāb to have failed to appoint any agent to inform everybody about an immanent or actual fulfilment of the liqā’ (Encounter with God) for which all were created (Per. Dalā’il, 31ff).

The Futurity of Prophethood and Divine Guidance.

It is today a central Bābī-Bahā’ī teaching that future divine messengers (al-rusul) or maẓhar-i ilāhī (divine manifestations) will, for many thousands of years, found and progressively renew the eternal religion of God. The Bāb’s claim to be the Sunni-Shī`ī messiah, the Qā’im/Mahdī and one in whom the liqā’ Allāh (Encounter/Meeting with God) finds fulfilment, did not prevent or inhibit his also predicting numerous future messianic advents of the perhaps originally Sufī figure man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh (Him whom God shall make manifest), in all of which the liqā’ Allāh (Divine Encounter) would find successive fulfilments (Goldziher, 1921 tr. Lambden & Walker 1992). This is indicated in a passage from the Bāb’s late Kitāb-i panj sha’n (`Book of the Five Grades’, 1850 CE) where the following words could be taken to indicate an infinite number1 of future theophanies of the Bābī theophanic messiah, man yuẓhiru-hu-Allāh:

.. And after the Bayān comes [the theophany of] man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh (He whom God will make manifest) [1]. And after man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh [1] man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh [2]. And after man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh [2] man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh [3]. And after man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh, [3] man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh [4]. And after man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh [4] man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh [5]. And after man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh [5] man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh [6]. And after man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh [6] man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh [7]. And after man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh [7] man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh [8]. And after man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh [8] man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh [9] … (K. Panj-Sha`n, 314-5, cf. 397).

There is a similar passage of the Bāb to the above in his earlier Arabic al-Dalā’il al-Sab`a (Seven Proofs, c. 1849). Commenting on the Qur’ānic statement of Muhammad about past prophets (al-nabiyyīn; cf. the khatam al-nabiyyīn of Q. 33:40), he emphasizes that this indicates their essential oneness in promoting a single religion or Cause of God (amr wāḥid). This oneness continues from the Islamic era until that of the Bāb as the “Point of the Bayān. Thereafter from the Point of the Bayān it continues until the era of the first messianic man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh (Him whom God shall make manifest”) and subsequently to another man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh and yet another man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh. This messianic theophany, the Bāb then states, will continues on “unto the end (ākhir) which knoweth no end (ākhir)” (Ar. Dala’il, p. y = 10).

The position of the Bāb is thus the exact opposite of the Islamic proponents of the doctrine of the finality of prophethood. The mention of nine or of an endless succession of theophanies of man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh (He whom God will make manifest), most likely indicates their endless future realization. Towards the end of his life in his Haykal al-dīn (Temple of Religion, 1266/1850), the Bāb made increasing mention of "He whom God will make manifest". He variously indicated the time of his messianic advents at after nine (=1269/1852), nineteen (= 1279 =1862-3) or between 1511 (abjad of Ar. ghiyāth = `the Assistance’) and 2001 years (abjad of Ar. mustaghāth = `The One Invoked for help’) from 1260/1844. These latter figures were understood by Bahā’-Allāh as either numerically and/ or messianically suggestive Names of God, sometimes indicative of the nine (1844-1852-3 CE) or nineteen year period (1844-1863 CE), sometimes of non-chronological import. Certain of these diverse messianic datings are also viewed as allusions to the times of further future, post-Bābī-Bahā’ī era theophanies (see Bahā-Allāh, Lawḥ-i Khalīl Ibrahim Muballigh Shirazi, pp.1-30; `O Thou Creator’ Hebrew Univ. ms.).

Khātamiyya and the Liqā’ Allāh in the writings of Bahā’-Allāh

“The mystery of this theme (khātamiyya, “the sealedness of the prophets”) hath in this Dispensation (ẓuhūr)… been a sore test (mumtaḥan) unto all mankind” (KI: ¶ 172-3, pp. 107-8 trans. 162). [1]

It has been indicated above that the Arabic word khātam in khātam al-nabiyyīn (Q. 33:40) need not signify "seal" implying "last" of prophets. For Bahā’īs it more appropriately indicates Muhammad as the best, the supreme "acme of the prophets" during the era before the yawm al-qiyāma (Day of Resurrection) when the liqā’ Allāh, through a messianic maẓhar-i ilāhī (Manifestation of God), would be realized. Like the Bāb, Baha’-Allāh in his Kitāb-i īqān (`The Book of Certitude) specifically deals with the issue of the khatam al-nabiyyīn (seal of the prophets) in the light of the liqā’ Allāh (encounter with God).

The deep theological senses of the eschatological realization of the liqā’Allāh/al-Rabb and of the future vision of the Lord God, are central to the religion founded by Bahā’-Allāh. He proclaimed the depths of this subject in the light of his theophanological claims expressed in many of his major books and scriptural Tablets. He presented his Bahā’ī religion as being established on the Day of God, the era of the presence, meeting or encounter with God (liqā’ Allāh). Bahā’-Allāh many times states that the era of the liqā’ Allāh (Encounter with God) was and will be realized through the messianic Parousia (presence) of the theophanic maẓāhar-i ilāhī (Divine Manifestations) who renew religion from age to age. Today the liqā’ Allāh (Divine Encounter) is thought by Bahā’īs to have come about through the persons and religious teachings or missions of the Bāb and Bahā’-Allāh, They are both seen to represent the indirect theophany of the unknowable Godhead on the Day of God (yawm Allāh). Throughout the forty-year period of his prophetic mission (1852-1892), Bahā’-Allāh often referred to, and commented upon, the liqā’-Allāh, the Encounter-Meeting with God. Only a few scriptural texts dealing with this important subject can be surveyed here.

Rashḥ-i `amā’ (“The Sprinkling of the Theophanic Cloud”, 1852-3).

In the fourth couplet of his early poem, the Rashḥ-i `amā’, there is reference to “a Wave of the Ocean of the Meeting with God’ (mawj-i liqā)” through which “the Sea of Purity (baḥr-i sifā)” cried out. This perhaps indicates the realization of the eschatological divine theophany through the liqā’ Allah (Encounter with God) in the Bab and/ or Bahā’-Allāh himself.

Lawḥ al-Ḥurūfāt al-muqaṭṭa`āt (Tablet on the Isolated Letters, c. 1858).

Another early writing of Bahā’-Allāh dealing with the issue of the khātam al-nabiyyīn (Q. 33:40b) is his testimony to the theophanic mission of the Bāb in his Lawḥ al-Ḥurūfāt al-muqaṭṭa`āt. The Bāb, it is said, came with all manner of "dazzling proofs", though the people "waxed proud" in their denial. This despite the qur’ānic promise of the liqā’- Allāh (Meeting-Encounter with God). When God sealed prophethood (khatama al-nubuwwa) through Muhammad (Q. 33:40) "he gave the servants the glad-tidings of the encounter with Him [God]" and the matter was "definitively resolved" (khatama al-makhtūm). In the person of the Bāb, "God came [unto them] in the shadows of the clouds (fī ẓulal al-ghamām, Q.2:210), breathed into the Trumpet of the Cause (nafakha fī ṣūr al-amr; cf. Q.18:99; etc), split the Heaven asunder (inshaqqat al-samā' cf. Q.55:37; 69:16; 84:1) and crushed the mountains to dust (Q.56:5; 69:14, etc). At this, symbolically speaking, all “retreated back upon their heels” (cf. Q.3:144; 6:71) (Ma’ida, IV: 65). In the Lawḥ-i Ḥurūfāt, Bahā’-Allāh continues to argue that in spite of the theophany of the Bāb, the people acted like Jews and Christians. They continued to await the realization of the promises and the eschatological liqā’ Allāh (Divine advent).

Tablet to `Alī Muhammad Sarrāj (c.1867 CE)

In his decade or so later and lengthy Persian Tablet to `Alī Muhammad Sarrāj (c.1867 CE), Bahā’-Allāh himself mentions the subject of the obscurity of eschatological prophecies in Abrahamic religious scripture. He highlights the supremely clear implications (aṣraḥ al-kalimāt) of finality in the khātam al-nabbiyyīn (Q. 33:40) but thinks it has become an unfortunate, unacceptable veil, inhibiting post-Islamic faith in another supreme agent of God. Despite its implications of finality, Baha’u’llah has it that pure-hearted persons still came to true faith in the Point of the Bayān (bi-irfān nuqṭa-yi bayān = the Bāb). Indeed, he adds, such pure-hearted persons so comprehended the matter of khātimiyyat ("sealedness") that they would happily acknowledge the appearance of a "prophet" (nabī) "from the beginning which has no beginning unto the end which has no end" (Lawḥ-i Sarrāj, Ma’ida, VII: 28ff).

For the Bāb and Bahā’-Allāh, the qur’ānic khātam al-nabiyyīn in no way rules out the theophany of divinity on the eschatological "Day of God" (yawm Allāh). Even if it is taken to outrule the finality of the appearance of a post-Muhammad nabī (prophet) or even rasūl (sent one), it does not negate an eschatological theophany. Both the Bāb and Bahā’-Allāh claimed to be fully human yet fully divine maẓhar-i ilāhī (Manifestations of God) in a way that transcends issues revolving around the various limiting meanings of the khātam al-nabiyyīn. In fact Bahā’-Allāh so transcended these matters that in numerous theophanological passages he presents himself as the divine figure who commissioned or sent out the nabī (Prophets) and rasūl (Messengers) of the pre-Islamic era. In an important Arabic Tablet of the Acre period, Bahā’-Allāh defends himself against accusations that he has contradicted the Muslim understanding of Q. 33:40b by stating:

You have assuredly confirmed [the truth] by what you have announced [in citing Q. 33:40b]. We do indeed testify that through him [Muhammad] messengership and prophethood (al-risāla wa’l-nubuwwa) were sealed up. Whomsoever after him [Muhammad] makes claim to such an elevated station is indeed in manifest error.... The carpet of prophethood (bisāt al-nubuwwa) has been rolled up and there has appeared the one who sent them out (arsal) [Bahā’-Allāh] in manifest sovereignty… (Untitled Tablet to Ḥasan or `Lawḥ-i Khātam al-nabbiyīn’).

Jawahir al-asrār (“The Gems of the Mysteries” (c.1861). [2]

The Arabic Jawāhir al-asrār (Gems of the Mysteries) of Bahā’-Allāh was written in Baghdad in c. 1277/1860-61 in response to questions posed by Sayyid Yūsuf Sidihi (Isfahanī), a pupil of the high-ranking Shī`ī cleric, the one-time marja` al-taqlīd (supreme Shī`ī authority), Shaykh Murtaḍā al-Anṣārī (d. Najaf 1864). It contains ten or eleven references to liqā’ (the encounter with God) and comments upon the theology of its end-time realization. The addressee is described as one “certain about the “Encounter with their Lord” (liqā’ rabbihim) at a time when the wayward failed to attain unto faith in the Bāb as “His Beauty” (jamāl) on the “Day of His Encounter” (yawm liqā’ihi) (Jawahir, 7, 25, cf. trans. Gems, 7, 40).

Referring to Muhammad as the illustrious “Point of the Furqān [Qur’ān]” capable of enabling his followers to enter the jannat al-liqā, the “Paradise of the Divine Presence/ Encouter”, Bahā’-Allāh describes the subsequent “Paradise on the Day of God” (jannat fī yawm Allāh) as supreme or “greater than every other Paradise” (a`ẓam min kull al-jinān). This is indicated by the fact that, prior to it, God “sealed the station of prophethood” (khatama maqām al-nubuwwa) through Muhammad as indicated in Qur’ān 33:40. After specifically citing this Qur’ānic verse, Bahā’-Allāh straightway reminds his readers that God promised in the Qur’ān that they would all attain the liqā’ (the Divine Encounter/Presence) on the Day of Resurrection” (yawm al-qiyāma). By this and by means of the Qur’ānic verses about liqā’, the greatness of renewed eschatological religion (`aẓimat ẓuhūr al-ba`d) as the supreme “Paradise” is indicated. Having made this point, Bahā’-Allāh registers the following blissful clarificatory salutation:

“Blessed be he who knoweth of a certainty that he shall attain unto the presence of [encounter with] God (bi-liqā’ihi) on that Day when His Beauty (jamāl) shall be made manifest” (Jawahir, 36ff, trans. Gems, 42ff),

Holding back from citing all the numerous and elevated Qur’ānic references to the liqā’ Allāh/al-rabb, to which he assigns a tremendous importance, Bahā’-Allāh singles out Qur’ān 13:2 which he quotes in full. Finally, but not exhaustively in this connection, it should be noted that in the Jawāhir al-asrār Bahā’-Allāh several times associates the liqā’-Allāh with the coming “Day” of the “latter resurrection” (qiyāmat al-ukhrā). As in the Bayān, he closely associated this with the messianic figure man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh (“Him whom God shall make manifest” (see Jawahir, 49, 62. trans. Gems, 37, 73). In this connection a beatitude is pronounced upon the person who experiences the liqā’-Allāh through this Bābī messiah:

“So Blessed be (ṭūba) the one who experiences his presence and attains unto the Encounter/Meeting with Him” (liqā’)!” (ibid).

[1] Note the following almost parallel passage in the Persian Seven Proofs (Dalā’il-i sab`a) of the Bāb : “The people of the Bayān … will be sorely tested (mumtaḥan) in man yuẓhiru-hu Allāh (Him whom God shall make manifest) (Per. Dala’il, 45).

[2] Here I shall cite the page numbers of the 2003 Arabic printing (2nd ed.) and the 2002 Gems translation (see bib.). References to liqā’ (encounter) can be found on the following pages Ar. 7/Gems 7; Ar. 18/Gems 21; Ar, 34/Gens 40; Ar, 36/ Gems 42-3 (twice); Ar. 37/Gems 43-4 (twice); Ar. 39/ Gems 47; Ar. 40/Gems 48; Ar. 49/ Gems 58; Ar. 62/ Gems 73.

The Kitāb-i īqān (Book of Certitude)

The around 1862 CE Persian Kitāb-i īqān (Book of Certitude) of Bahā-Allāh, contains many paragraphs clarifying theological issues, especially those surrounding the khātam al-nabiyyīn and the expected qur’ānic liqā’ Allāh/al-Rabb, the encounter/meeting with God. Such as view the eschatological liqā’ (Encounter) as naught but a general or fully theophanic Divine tajallī (divine “Self-manifestation”, “effulgence”, “glorious theophany”, etc cf. Q. 7:143) are offered a messianic perspective. The Kitāb-i īqān was written in reply to questions posed by a maternal uncle of the Bāb named Ḥajjī Mīrzā Sayyid Muhammad (d. 1293/1876’) and known as Khāl-i Akbar (The Greatest Uncle). He had specifically enquired about the traditional Islamic “signs” of the eschatological manifestation or theophany (zuhūr). This in the light of the messianic claims of the Bāb, including a clarification of khātam al-nabiyyīn and of the Qur’ānic liqā’ Allāh (Encounter with God). [1]

This question of the theophany, the liqā’ with God on the Day of Ressurection, is mentioned around 37 times in the `Book of Certitude’. Six or so of these references are found within cited qur’ānic verses, including Qur’an 2:188; Q, 29:23; Q, 2:46, 239; Q. 18:110 and Q. 13:2 (see esp. KI: ¶ 148-9; pp. 92-3, trans. 136f). In the Kitāb-i īqān, Bahā-Allāh himself notes that there are references after Qur’ān 33:40b to the future promise of the liqā-Allāh and states that there is “nothing more exalted (a`ẓam) or more explicit (aṣraḥ)” than liqā’ (the encounter with God/ attainment unto the divine Presence) in the Qur’ān (see esp. Q. 39:71; 40:15; 41:54, etc., Kassis Concordance, 743ff and refer KI: ¶ 181 p.112, trans. pp.169-70).

Numerous paragraphs in the Kitāb-i īqān deal directly or indirectly with the challenging subject of khātamiyya, the issue of the “seal of the prophets”. Bahā-Allāh states that people generally failed to understand the meaning of this subject. They were severely tested when this phrase obscured and challenged their understanding. This to the degree that many were deprived of the ever-unfolding providence of God through the coming of the Bāb. The exalted reality of the person of Muhammad, Bahā’-Allāh argues in the light of various Islamic traditions, was historically “timeless”, both “first” and “last” and not at all something “sealed”. The prophet is said to have declared his identity with all past prophets or messengers such as the first Adam, Noah, Moses and Jesus. Since Muhammad regarded himself as Adam, the “First of the Prophets”, it is not at all suprising that he legitimately saw himself as the “Seal of the Prophets”. This latter phrase was never meant to outrule the eternal succession of prophets who offered divine guidance. Like God Himself according to Qur’ān 57:3, the great Prophets are ever and always both the “First and the Last” (KI: ¶ 172ff., p.107ff., trans. p. 162ff).[2]

It is on these lines that Bahā’-Allāh in his Kitāb-i īqān and elsewhere, argues that khatām al-nabiyyīn was an important epithet of Muhammad. It underlines the elevated nature of the Arabian prophet but does not imply the absolute finality of prophethood. Understood with the sense of utter finality, Bahā’-Allāh states that khātam al-nabiyyīn degenerates into one of the hubristic subuḥāt al-jalāl ("veils of glory") which can severely hinder the realization of unfolding reality (KI: ¶ 175,p. 109, trans. 164-5).

Introducing the person of the Messemgers or Manifestations of God and their ongoing rejection throughout history by their wayward contemporaries, Bahā’-Allāh refers to the eschatological liqā’ (“the Divine Encounter” / “Presence”) as “the very essence of the liqā’ Allāh of God Himself”. Clarifying the Persian text here, Shoghi Effendi had it that the Divine Messengers are “His Face (liqā’)” (liqā’-i ū), the very “the Face of God Himself” (`ayn liqā’ Allāh) (KI ¶ 3 p. 2, trans. p. 3). The person of the Manifestation of God is presented as the quintessential embodiment of the liqā’ Allāh (Encounter with God), the divine Theophany. The importance of this theological interface between God and his Messenger (traditionally between “Him/It” and the subordinate “Him/It”), is repeated throughout the Kitāb-i īqān as the following few notes much suffice to further illustrate.

Islamic and Pre-Islamic Liqā’ (The Divine Encounter/Presence).

Observing the Jewish rejection of Jesus who is referred to as the “Beauty of Jesus” (jamāl-i `Isavi), Bahā’-Allāh states that the people failed to attain the liqā’-Allāh, the encounter with God, through this “youthful Nazarene” (javān-i nāṣiri). Worth noting in this connection, is the fact that various texts within the Gospels as well as many other New Testament writings and related apocryphal texts, apply prophecies of the Hebrew Bible about a Divine advent, the coming of of God, the Lord (Gk, kyrios) himself, to Jesus. [3] For Bahā’īs the liqā’ Allāh (encounter with God) was realized at the time of the advent of all pre-Bābī-Bahā’ī Manifestations of God including Moses, Jesus Muhammad and many others. They hold that the latter-Day liqā’ Allāh through the Bāb and Bahā’-Allāh, was echoed in the past though more fully fulfilled in recent times when the promised “Day” is believed to have come to pass (KI: ¶ 17 pp. 11-12, trans. 17-19).

Within the sacred books of the past, all were promised the liqā’ Allāh (Divine Encouter/Presence) and the ongoing receipt of deep knowledge `irfān (*gnosis”) through Him, through the recognition of Him (KI: ¶ 148 p. 91 p. 136-9). Such has been fulfilled in the past and is expected again; like the first and the second advents of Jesus. Bahā’-Allāh explains that devout Muslims had attained the nobility of the encounter with God (liqā’ Allāh) through the reviving, “sanctified breaths” (nafaḥāt-i qudsiyya) of Muhammad. They may now anticipate the challenge of the eschatological liqā’ Allāh in the Babi-Bahā’ī era of the Day of Resurrection (KI: ¶ 170, p.106 trans. 159-60).

Though, from the Bābī-Bahā’ī point of view, most Muslims came to reject or misinterpret meaning of the attainment to the liqā’ Allāh (“encounter/ presence of God”), it is an encounter referred to in the `Book of Certitude’ as “the utmost degree of ever-abiding grace” (fayḍ-i fayyāḍ-i qidam), the very “fullness of His absolute bounty” (kamāl-i faḍl-i muṭlaq) bestowed upon humankind (KI: ¶ 148, p. 91 trans. 136-7). Having said this Bahā’-Allāh cites five confirmatory qur’ānic `Liqā’-Allāh verses’ (Q. 29:23; 2:46, 49; 18:111 and 13:2) some touching upon its past rejection and/or its future realization. He comments that “No theme hath been more emphatically asserted in the holy scriptures (kutub-i samāvī)” (KI: ¶ 148-9, p.92 trans. 138f).

Bahā’-Allāh rejected the interpretation of liqā’ Allāh as an eschatological tajallī Allāh (“the effulgence of God”) on the qiyāmat or `Day of Resurrection’. Such an understanding of Divine Self-revelation is in fact only a general divine disclosure, something already evident within everything as a “Universal Revelation” (tajallī-yi `āmm). God is actually ever-present. On this level everything is actually a “locus” (maḥall) and manifestation (maẓhar) of the divine tajalli (Effulgence/ Theophany) of the “Sovereign of Reality” (sulṭān-i ḥaqīqi), expressing elements (āthār) deriving from the Sun of the divine Theophany, the “Source of all splendour” (shams-i mujalla). [4] On this general level these divine effulgences or reflections, originated with or are centered within the elevated Deity-reflecting Messenger or `Manifestation of God (maẓhar-i ilāhī) (KI: ¶ 149, p.92 trans. 139-141).

To attempt to clarify this further, Bahā’-Allāh argues that the eschatological liqā’ Allāh (the Divine Encounter/ Presence) cannot, as some Sufis have maintained, merely be an expression of the “Most Holy Outpouring” (fayḍ-i aqdas), a specific or direct Divine Self-revelation (tajallī-yi khāṣṣ) of the unknowable Essence of God Himself. [5] If the liqā’-Allāh, on the other hand, were to be considered to be an indirect or secondary Divine revelation (tajallī-i thānī), a “Holy outpouring” (fayḍ-i muqaddas), this would not be expressive of the qur’ānic eschatological liqā’-Allāh (encounter with God) since it would be something that has long been realized within the realms of being, “in the realm of the primal and original manifestation of God (`ālam-i ẓuhūr avvaliyya)” through His Chosen Messengers.

This latter mode of tajallī (Divine effulgence) applies to the supremely elevated persons of the divinely inspired Manifestations of God, His Prophets (anbiyā’) and chosen ones (awliyā’) who reveal “the unchangeable attributes and names of God”. They most perfectly represent God for humanity. It is thus the case that attaining the presence of these holy Luminaries (liqā’-i anvār-i muqaddasa), the liqā’-Allāh, the encounter or “Presence of God” Himself is attained. In its fullness, however, the Divine “encounter” or “presence (liqā’) is possible only on the Day of Resurrection (qiyāmat), which is the Day of the rise of the Personal representative of God Himself (qiyām nafs Allāh) through His all-embracing Revelation”, His latest eschatological manifestation or theophany (KI: 150f, pp. 93-4 trans. 141f.). As the Bāb had frequently stated, the liqā’ of the Divine Manifestation is the essence of the liqā’ Allāh (KI: ¶ 170, p.106 trans, 159f.). The promise of the eschatological liqā’, the encounter/presence of God is, in reality, attainment unto the jamāl (“Beauty”) of the maẓhar-i ilāhī (Manifestation of God) in the person or temple of His theophanic Manifestation (dar haykal-i ẓuhūr-i ū) (KI: ¶ 182, p. 170, trans. 106).

Kitāb-i Aqdas (“The Most Holy Book”).

A centrally important reference to the liqā’ Allāh/al-Rabb is found in the c. 1873 `Most Holy Book’ of Bahā’-Allāh. This encounter, it is stated, is possible on the eschatological “Day of God” being the cause of great rejoicing. We thus at one point read in this weighty Arabic text :

The Promised One (al-maw`ūd) hath appeared in this glorified Station, whereat all beings, both seen and unseen, have rejoiced. Take ye advantage of the Day of God (yawm Allāh). Verily, to meet Him (Iiqā’ihi) is better for you than all that whereon the sun shineth, could ye but know it” (Aqdas ¶ 88).

Lawḥ-i Jawhar-i Ḥamd (“Tablet of the Essence of Praise”),

In his late Acre period Lawḥ-i Jawhar-i Ḥamd (“Tablet of the Essence of Praise”), Baha’u’llah has much to say about Babi-Baha’i theology (see INBMC 35: 161-168). As in his Jawāhir al-asrār, he quotes Q. 13:2 and comments in some detail about the liqā’ al-rabb (“encounter with the Lord”) as the meeting with the eschatological maẓhar-i ilāhi (“Manifestation of God”). The Pre-Existent Divine Essence (dhāt-i qidam) has never nor will ever be attainable through His Hidden and Sanctified Attributes at the time of the liqā’ Allāh (Encounter with God). As in the Kitāb-i īqān, Bahā’-Allāh states that such as are unaware of deep truth (`irfān) in their tafsīr (commentary upon this qur’ānic verse), inappropriately view the liqā’ (Divine encounter) as being indicative of a general Divine Effulgence (tajallī-yi ū) on the Day of Resurrection. The Day of Resurrection (qiyāmat) is actually the time of the rising up of the Manifestation of the Logos-Self of God (qiyām-i maẓhar-i nafs Allāh) who is both the Qā’im (the `Supportive’ messianic Ariser) and the Qayyūm or subordinate deity Self-Subsisting (Jawhar, 18-19). [6]

The Lawḥ-i Shaykh or `Epistle to the Son of the Wolf’

In his c. 1890 Lawḥ-i Shaykh Muḥammad Taqī Mujtahid-i Iṣfahānī [Najafī] or as Shoghi Effendi entitled this quite lengthy Persian work of Bahā’-Allāh, the `Epistle to the Son of the Wolf ‘, there is an important reference to Muhammad as the “seal of the Prophets” (khatam al-nabiyyīm) and to his prediction of the eschatological vision of the Lord (see the Qur’ānic refs. cited above):

“What explanation can they give concerning that which the Seal of the Prophets (Muhammad) … hath said? : “Ye, verily, shall behold your Lord (rabb) as ye behold the full moon (al-badr) on its fourteenth night” (ESW: 50/ trans. Shoghi Effendi, 41-2). [7]

In later paragraphs of this `Epistle to the Son of the Wolf’, Bahā’-Allāh cites and succinctly interprets a cluster of fifteen qur’ānic verses (in Persian termed the āyat-i liqā’, `the verses of the Encounter’) [8] most of which contain a reference to the liqā’ (“encounter”. etc) with God. They are seen as expressive of the latter-day promise of the divine theophany or “Presence” of God/the Lord”, [9] a presence actualized on earth and the realms beyond through the divine Manifestation of God. God Himself cannot be literally seen. He states that the proimse of the liqā’ (encounter / meeting / presence) of God, the Lord, is explicitly recorded in all past sacred scriptures or books. It has a personal, individualistic or Logos-centered interpretation (maqṣūd-i liqā’ liqā’ nafsī ast) closely related to the one who is the Qā’im-Maqām, the divine Messenger, His “Viceregent” amongst men (so Shoghi Effendi, see ESW: 139/ trans. 118).

The Biblical and Post-Biblical `Coming of God’.

Perhaps informing the above-cited qur’ānic verses and traditions about an eschatological advent of Divinity, the Hebrew Bible and many post-biblical Jewish literatures contains texts indicative of an eschatological theophany (“coming of God”) of the person of the Divine or as “God”, the “Lord” in his “Glory” (Heb. kavod Ar., Bahā’). Praying in Aramaic that Jesus Christ as the “Lord” might soon return or come again as a divine figure, early Christians uttered the exclamatory μαράναθά, maranatha (“Come, Lord!”) prayer (Aramaic Mar = Greek Kyrios = Lord ; see 1 Cor. 16:22; cf. Zech 14:5; Jude 1 Enoch 1:9’ Didache 10:6).[10] Some such biblical texts are cited by Bahā’-Allāh in many of his alwāḥ (scriptural writings or `Tablets’) as being predictive of himself as a divine Manifestation (not the essence of God Himself):

“Out of Zion, the perfection of beauty, God hath shined. 3 Our God shall come, and shall not keep silence” (Psalm 50:2-3).

“… the Lord my God shall come, and all the saints [holy ones] with thee. (Zech 14:5b).

“And the glory of the LORD shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together: for the mouth of the LORD hath spoken it… Behold, the Lord GOD will come with strong hand, and his arm shall rule for him” (Isaiah 40: 5, 10 cf. Rev 22:20).

Like Jesus Christ in the Gospels and Christianity, the Bāb and Baha’-Allāh have been regarded in Bahā’ī sacred writings, as manifestations of the “Lord” or “Lord God”, [11] the latter as the master, owner or “Lord of the Vineyard” (refer Mark 12: 9; Matthew 21:40; Luke 20: 15b). [12] These end-time theophanoloical predictions are of central interest providing important background to the Qur’ānic Liqā’ Allāh.

At this point it should be mentioned that there exists a theologically important, quite lengthy Arabic scriptural Tablet of the son and successor of Bahā’-Allāh entitled `Abd al-Bahā’ (1844-1921). It is a text which might be called the Lawḥ-i Liqā’ Allāh or `Tablet of the Divine Theophany’. It contains materials about the eschatological coming of God through his representative (as Baha’u’llah, the Manifestation of God), the fulfilment of the Qur’ānic liqā’ Allāh predictions, and related Islamic ḥadīth texts (see`Abdu’l-Bahā’ Makātib 1: 102-108). There are clear references within it to the widespread Abrahamic religious texts about the eschatological theophany or `Meeting with God’:

Know that the aforementioned beatific vision on the Day of God (ru’yat fī yawm Allāh) is mentioned in all the scriptural scrolls (al-ṣaḥā’if) and sacred writ (al-zubr); in the tablets (al-alwāḥ) which have been sent down from heaven unto the prophets (al-anbiyā’) throughout ancient times (ghābir al-azām), during bygone eras (al-`uṣūr al-khāliyya), and from the primordial centuries (al-qurūn al-awwaliyya). Every single prophet (nabīyy) among the prophets (al-anbiyā’) announced unto his people the glad-tidings of the Day of the Theophany [Meeting with God] (yawm al-liqā’). Consider then the specific references found in the Gospels (al-injīl), the Psalms (al-zubūr), the Torah [Pentateuch] (al-tawrat) and the Qur’ān.

God Himself says in the Qur’ān:”Know ye that thou shall indeed meet Him (mulqū-hu)!” (Q.2:223b) on the Day of Resurrection (yawm al-qiyāma)”. And also He says [in the Qur’ān], “Lost indeed are such as cried lies to the Meeting (liqā’) with their Lord (rabb) [God]” (Q. 6:31; 10:45; 23:33; 30:8b; 32:10; 41:54, etc). And again He says [in the Qur’ān], ”Perchance thou might be assured about the Meeting (liqā’) with thy Lord (rabb)” (Q. 13:2b. cf. 6:154, etc). (`Abd al-Bahā’, Makatib 1:103-4). [1]

Having cited or paraphrased these Qur’ānic verses, `Abdu’l-Baha’ quotes a summary version of the above mentioned Prophetic ḥadīth about a future vision of God, the Lord, like the sight of the full moon in the middle of the month. He continues to cite several passages from writings attributed to Imam `Alī ibn Abī Ṭālib (d.40/661) expressive of the beatific or eschatological vision of God. They are understood to apply to the person of Bahā’-Allāh. Though details cannot be spelled out here, it must suffice to translate a few lines pertinent to the subject of liqā’, the meeting or encounter with God and its Baha’ī exegesis:

Now as regards the essence of the enquiry [about the eschatological theophany] and the reality of the matter, it is that the Liqā’ (Meeting with God) is a matter clearly proven, firmly established and specifically set down in the sacred scrolls (al-ṣuḥuf) and the scriptural Tablets (alwāḥ) of the Living One (al-ḥayy), al-Qayyūm (the Deity Self-Subsisting) [Bahā’u’llāh]. This is assuredly the sealed wine (al-raḥīq al-makhtūm) whose seal is of musk … The Paradise of the Encounter with God (jannat al-liqā’) is the Most Elevated [Bābī] Paradise and the All-Glorious [Bahā’ī] Kingdom (malakūt al-abhā)” (`Abd al-Bahā’, Makatib 1:104-6).

For the Arabic text and my full translation of this `Lawh-I Liqā’ (Tablet of the Divine Theophany) of `Abd al-Bahā’ see this Hurqalya Publications Website at :

Arabic text from Makatib-i Hadrat-i `Abdu'l-Baha', Vol. 1:102-108. PDf. L-Liqa-Makatib-1-102f.pdf

The Lawḥ-i Liqā’ (“Tablet of the Meeting with God”) of Bahā’-Allāh.

In a volume of scriptural Tablets (alwāḥ) of Bahā’-Allāh complied by the Persian Bahā’ī apologist `Abd al-Ḥamīid Ishrāq Khāvarī (d. 1972), there exists an Arabic text provisionally entitled Lawḥ-i Liqā’ (“Tablet of the Meeting with God”; see Mā’ida, VIII: 167-168). It opens with a prefixed “He is [God is] the Eternal (huwa al-baqī)” and continues: