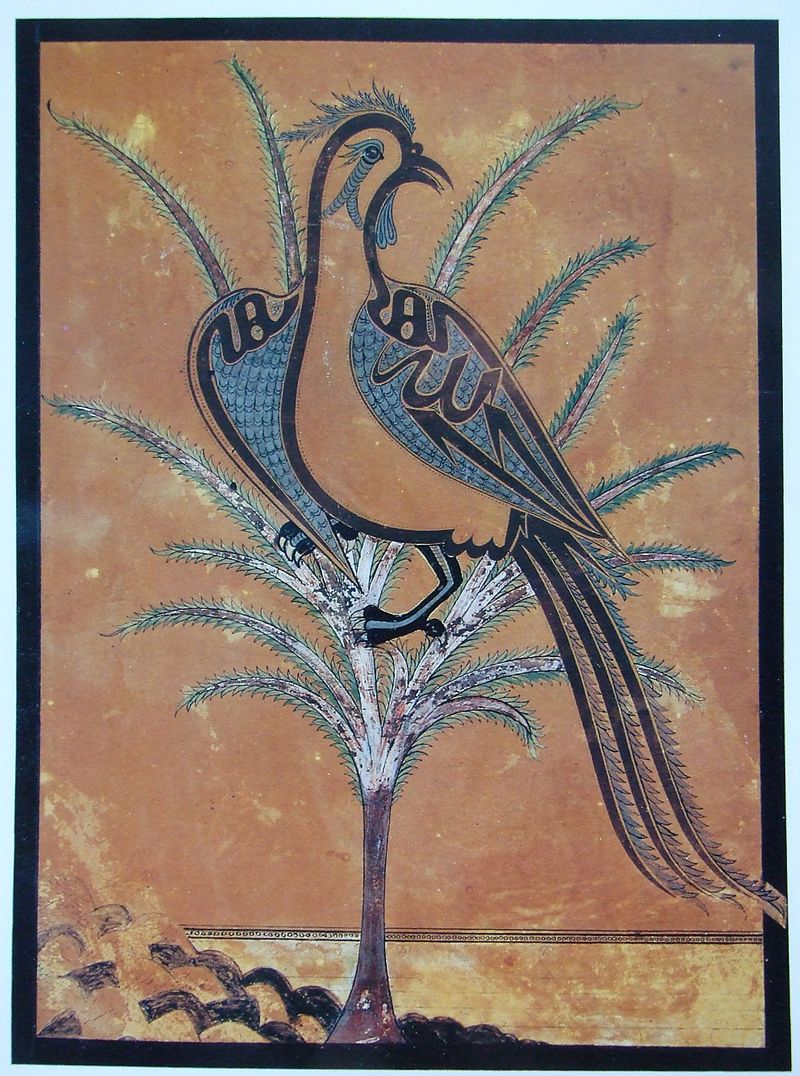

قصيده عز ورقائيه

Qaṣīdih `izz varqā'iyya ("The Mighty Ode of the Dove", c. 1272/1855).

Stephen N. Lambden - 1990s - being revised and updated 2014.

TB2B: 04

(Ar.) Qaṣīdih `izz varqā'iyya ("The Mighty Ode of the Dove", c. 1272/1855).

During his residence in Sulaymaniyya (Iraqi Kurdistan) Bahā'-Allāh, in view of the very considerable reputation for mystic learning he had gained among resident Sufis, was invited to compose an ode in the metre and rhyme of Ibn al-Fāriḍ's al-Qaṣīda al-ṭā'iyya ("Ode Rhyming in Tā'"), also known as the Naẓm al-sulūk ("Poem of the Way"). Fn.1 This led Bahā'-Allāh to compose around 2,000 Arabic verses in an "irregular catalectic tawīl metre" and to select 127 of them for circulation. Bahā'-Allāh apparently considered all but 127 of the verses he composed beyond the capacity or comprehension of his devotees; possibly because they only thinly veiled his Bābī orientation or secret messianic claims. Alternatively, it is worth noting that in certain circles it was not considered proper for the qaṣīda to be excessively long (e.g. more than 175 couplets) or too short (e.g. less than 25 couplets) (see D. Forbes, Persian Grammar, London 1920, 25). It should also be noted at this point, that Bahā'-Allāh's comments on select lines and terms occurring in his Qaṣīda al-warqa'iyya probably date from the late Baghdad or early Edirne [Adrianople] period (1857-1866?). The text is printed in AQA III:196f along with the Qaṣīda itself.

Translations

Translations :

Hippolyte Dreyfus (1873-1928).

- (1) Hippolyte Dreyfus (Fr.), Qasida-yi Varqa'iyya. French Trans. in L'oeuvre de Baha'u'llah. Vol. X:XXf. Paris : Ernest Leroux, Bd. I 1923, Bd. II 1924, Bd. III 1928.

- (2) When lecturer in Islamic Studies at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne (1982-87; England, UK) Denis MacEoin translated the whole of the Qaṣīda into English for the Baha'i Studies Bulletin (ed. Lambden, Newcastle upon Tyne). See Denis MacEoin, `A Provisional Translation of the Qaṣīda al-warqā'iyya' in BSB. 2:2 (198X) pp xx-xx. See BSB2 this website.

Denis MacEoin

- Bahā'-Allāh’s al-Qaṣīda al-Warqā'iyya (Qaṣīda-yi Varqā'iyya: An English translation. p.7f.

PDf. DM-Warqaiyya.pdf Ms. / Reduced Qasida al-Warqa'iyya-DM.Tr.pdf

PDf. DM-Warqaiyya.pdf Ms. / Reduced Qasida al-Warqa'iyya-DM.Tr.pdf

Juan Cole,

- al-Qasida al-warqa'iyya : further Comments. BSB 2:3 (1983) 68f. Trans.

PDf. al-Qasida al-Warqa'iyya-JC.pdf

PDf. al-Qasida al-Warqa'iyya-JC.pdf

- (3) Juan Cole made a translation of the `Ode of the Dove' in 198X which is referred to in the BSB article and may be consulted at : Add

Juan Cole and Denis MacEoin Exchanges:

- The Cole-MacEoin exchanges on the al-Qaṣīda al-Warqā'iyya originally published in the BSB. 2:4 (1984), 44FF. = Exchanges on Bahā'-Allāh's al-Qaṣīda al-Warqā'iyya (Qaṣīdi-yi Varqā'iyyih).

PDf. JC-DM-Qasida.pdf

PDf. JC-DM-Qasida.pdf

Brian Miller

Qasidih-yi Varqa'iyyih ("Ode of the Mighty Dove").

- (4) Brian A. Miller established a semi-critical text, translated and commented upon aspects the Qaṣīda in the course of researching his doctoral thesis (UCLA. Berkeley, CA, USA): “The Lover’s Way: A Critical Comparison of the ‘Nazm al-Suluk’ by Ibn al-Farid with the ‘Qasidiyyi-Varqa’iyyih’ by Bahá’u’lláh.” Miller also delivered a paper upon this Qaṣīda at USA MESA conference in 2001. He plans to publish a revised version of his researches on the `Ode of the Dove' sometime soon.

Some Introductory Notes,

Stephen Lambden 1980s.

The "Mighty Dove's Ode" which has been well-characterized as a "fusion of Sufi mysticism with Bábi theological and eschatological teachings" (Cole, `Bahá'u'lláh and the Naqshbandi Sufis',198X:9). In the first part of the `Dove's Ode' Bahā'-Allāh lauds the dazzling beauty of a celestial maiden, his divine Beloved (lines 1-16). The female divine Beloved of the Qaṣīda is the locus of spiritual perfections. She plays a role in the eschatological Bābī drama and may be symbolic of Bahā'-Allāh's own celestial self. His quest for union with her may express his desire to announce his own secret divinity. In the opening lines Bahā'-Allāh associates her with the realization of eschatological events and draws on Moses-Sinai motifs in order to underline her exaltedness. It was on account of her radiance that the ṭūr al-baqā' ("Mount [Sinai] of Eternity") was made manifest (line 5a). The fire of her countenance and his qa da (or "love") led to the purification of the "Logos-Soul of the Speaker" (= Moses, nafs al-kalīm); the divine Maiden is identified with the Fire of the Sinaiatic theophany which burned away Moses' human limitations (line 8b). In commenting on this imagery, in line 8 of his Qaṣīda, Bahā'-Allāh has written an interesting mystical midrash on the (loosely) commissioning of Moses as detailed in the Qur'án:

In this highly allegorical treatment of Moses' experience of the divine, the Israelite Prophet becomes a type or model of the mystic wayfarer who should so strive that their whole being becomes irradiated with the divine effulgence (tajallī). The eternal Reality that is the interiority of Moses is the locus of divinity. Moses' outer words and actions as detailed in the Qur'ān express his transcendence of outer reality in the quest for mystic union.

In part II of his Qaṣīda Bahā'-Allāh laments his separation from the divine Beloved and pleads for mystic union (see lines 17-36). In expressing his burning desire for this union he makes mention of the "fire of the Friend (nār al-khalīl), the blazing furnace into which Abraham (= "the Friend") was cast:

"Compared with my burning, the fire of the Friend is but a torch" (line, 26b)

Part III (lines 37-61) of Bahā'-Allāh's Qaṣīda consists of the response of the divine Beloved to his plea for mystic union; she "rebukes him for his presumption, stresses her exaltation, accuses him of mistaking limited attributes for her unlimited essence and calls on him to seek martyrdom in her path" (see Cole, art. cit., 14). In underlining her exaltedness the divine Beloved represents herself as one the fire of whose love is more intense than the fire-brand perceived by Moses (line 42b, see Q. 20:10, comm. in AQA III:xxx) and the source of the radiance of Moses' snow-white hand/palm :

"[It was] from my Palm [Hand] that the Radiant Palm [Hand of Moses] was irradiated [lit. drawn near]" (line 43b).

In his comments on this (above) hemistitch (see AQA III:204) Bahā'-Allāh refers to Qur'ān 20:22 (+ Q. 27:12, 28:32)

The divine Beloved also identifies herself with the divine Being at whose glance (see Q.7:43) the archetypal Moses swooned away and on account of whose brilliance the Sinaitic mountains were leveled:

"At my glance the Moses of Eternity swooned away, and at a flash from me the Sinai of the Mountains was leveled" (line 46). Fn2.

In part IV of his Qaṣīda (lines 62-97) Bahā'-Allāh defends himself against the divine Beloved's charge of his unworthiness for mystic union. He represents himself as one ready to suffer all manner of oppression and indignity for her sake and dwells on the intense tribulations he has already endured. In so doing he "identifies his plight with that of holy figures and prophets of the past";

"The grief of Jacob and the suffering of Joseph, the pain of Job and Abraham's fire. The regret of Adam and the separation of Jonah, and the outcry of David and the lamentation of Noah. The separation of Eve and the burning of Mary, the tribulation of Isaiah and the suffering of Zachariah.. From the sprinkling of my sadness, there befell them all what befell them, from the overflowing of my grief, there appeared every affliction." (lines 72-5). (trans. MacEoin BSB 2:2, 11[adapted]).

In these lines the grief of Jacob is that which he experienced as a result of his separation from Joseph (see Q. 12:84) whose own imprisonment is also alluded to (see Q. 12:33ff). Job's afflictions are referred to in Qur'ān 21:83 and elaborated upon in various Islamic literatures (see below on the Lawḥ-i Ayyūb). Abraham's fire is that of the furnace into which he was believed to have been cast (cf. above on Qaṣīda line 26b). Adam was given to mourning and regret as a result of his expulsion from Paradise.

Dhu'l-Nūn, identified by Bahā'-Allāh as Yūnus (Jonah, Q. 37:139f; 68:48f; cf. 10:98; 4:163; 6:86?) "went forth enraged" and heedless of God's "power over him" according to Qur'an 21:87. David and Noah, Bahā'-Allāh himself comments, "lamented a great deal". The tale of Noah is well-known (frequently told in the Qur'án): as for the matter of David and his crying out, it is clear from the Psalms (zabūr) how much vexation he endured and to what extent he was afflicted by it."

Eve wept much, for 40 days or more according to the ḥadīth and Qisas al-anbiya' literatures, when, on the expulsion from Paradise, she was separated from Adam. The burning agony of the Virgin Mary resulted from her being pregnant with the `fatherless' child Jesus (see Q.3:35;19:16f).

Isaiah's tribulations are not mentioned in the Qur'ān though Jewish, Christian and Islamic sources picture him, in one way or another, as an Israelite prophet who suffered much and was martyred by being sawn in half. Shī`ī sources relate how the Israelites persecuted Isaiah for his prophecies and rebukes. He sought refuge by hiding in a tree but Satan held the fringes of his garment so that he could be seen and he was cut through with a saw (EJ 9: col. 68 and Biḥār al-anwār, 14:162); This account was handed down by Wahb ibn-Munabbih and is rooted in Jewish sources (on which see, for example, The Martyrdom of Isaiah [Part of the Christian apocalypse The Ascension of Isaiah] trans., in R. H. Charles, The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament, Vol.II ( ), p. f ; cf. EJ 9:71-2, and L. Ginsberg, Legends of the Jews, Vol. IV:277f and Vol. VI:374. n.103). By the Zechariah who suffered, the father of John the Baptist is doubtless intended (Q. 3:38-41; 19:2-12; 21:89fcf. 3:37; 6:85). Islamic sources also record the martyrdom Zechariah the father of Yaḥyā (= John the Baptist).

Part V (lines 98-127) of the Qaṣīda in which the divine Beloved urges Bahā'-Allāh to "go beyond the limited truth he has found" and again underlines her sanctified transcendence contains a few points of prophetological interest. The celestial female expresses her exaltedness by claiming that the theophanic splendour of Sinai (abhā' bahā al-ṭūr) is an inadequate expression of her divinity:

"The most glorious splendor of Sinai is to me mere rubbish" (line 100a).

She claims that her interior reality is the source of divine revelation; the locus confirmatory of the "heavenly writ" (zubur al-samá'). Her "scroll" (sahifa) is the source of the revelation of the "radiant scrolls" (ṣuḥuf al-saná') (see line 106). The "Sinaitic Throne" (`arsh al-ṭūr) is too narrow a celestial locale for the magnanimity of her being (line 111b [such may be the sense of this line]). Sinaitic motifs are again drawn on in expressing the elevated holiness of Bahā'-Allāh's divine Beloved.

The prophetological motifs in Bahā'-Allāh's Qaṣīda are illustrative of his considerable familiarity with qur'ánic stories of the prophets. In commenting on part IV of this work Cole has written that the reference to the non-qur'ánic prophet Isaiah (in line 74b) "betokens [Bahā'-Allāh's] familiarity with the Bible" (Cole art. cit. p. 17) though this bypasses the many extra-qur'anic Islamic sources in which Isaiah is a not insignificant figure (see Qisas al-anbiyā' ; Majlisi, Bihar, ). Whether or not Bahā'-Allāh had access to the Bible prior to the mid 1850's cannot be confidently asserted on the basis of the Qaṣīda prophetology.

Footnotes

Fn.1 = On the Egyptian mystic Ibn al-Fāriḍ (1181-1235 AD) and his Qaṣīda see, for example, R. A. Nicholson, Studies in Islamic Mysticism (Cambridge: CUP 1921) and A. J. Arberry The Mystical Poems of Ibn al-Farid (London: 1952) and The Poem of the Way (London: 1952).

Fn.2 trans., MacEoin (BSB 2:2, 10). This verse is based on Qur'ān 7:143 (see AQA III:204 for the comment of Bahā'-Allāh). The following line of the Qaṣīda (line 47) may allude to Jesus' power of resurrection