Islamo-Biblica and Islamicate pseudo-biblical and pseudepigraphical writings.

Stephen Lambden UCMerced.

1980s ... In progress. Last updated 12-01-2017.

Islamic pseudepigraphical texts and biblically ascribed writings.

Pseudepigraphical texts and writings, are not simply “pseudo-writings” but highly valued non-canonical Jewish or Christian (or other) texts ascribed to biblical and other worthies, sages, philosophers and kings or rulers. A pseudepigraphon (sing. pseudepigraha) is a pseudonymous work of this kind. There exists a huge amount of apocryphal and pseudepigraphical literature ascribed to biblical and related Abrahamic figures as well as other mythical or non-historical figures who stand outside of these traditions. The Jewish and Christian pseudepigrapha have existed for more than two millennia in a massive array of semitic and other languages such as Hebrew, Aramaic, Syriac, Ethiopic, Greek, Arabic, Persian, etc. Many were written or translated between the 4th cent, BCE and the pre-Islamic centuries CE though this body of literature also post-dates Muhammad (c. 570-632) and Islam in new forms. There is a massive sometimes biblically related Islamic pseudepigraphical literature of great interest, though it has been little studied or translated.

Whatever their provenance and alleged authorship, pseudepigraphical texts cannot simply be viewed as mere “pseudo-writings” falsely ascribed to prophet figures and sages of past eras. Rather, they should viewed today as one time highly-valued sacred writings deemed fit to have been divinely revealed to prominent prophets, sages or fountainheads of divine wisdom and prophetic insight. Many such writings within the pseudepigraphical canon, have been treasured for centuries by individuals and communities who drew inspiration and knowledge from these sometimes secreted writings. That they stood outside a given `authorized’ canon did not, in the eyes of many religionists, denigrate them in any way. Canonicity was not always, if it existed at all, a matter of consensus. A sacred text or great or stupendous magnitude would have no place in a canon fit for the masses or for the contemplation of the generality of religionists.

Islamic pseudepigraphical texts and writings are numerous. They may have biblical-qur’ānic or another ascription, though they often exhibit little or no concrete biblical basis or substrate.[1] They might be labeled neo-biblical [2] or proto-qur’ānic in the sense that they are Islamic creations often modeled on and reflecting the form or content of the Qur’ān. Many sayings ascribed to biblical figures are found in Islamic sources as are Islamic versions of biblical books and portions thereof, sacred paragraphs or pericopae. Numerous apologetic and interpretive Islamo-biblical citations echo Jewish Aramaic Targumic renderings which translate and make the Biblical Hebrew text meaningful for succeeding generations. Islamo-biblical and neo-biblical texts are no more “false” than Christian generated pseudepigraphal writings, recreations and re-translations of texts within the, Hebrew Bible and expressive of the Jewish tradition.

This is illustrated in many ḥadīth qudsī traditions such as are found, for example, in ḥadīth Arba`ūn (Forty Hadīth) compilations. One might in this respect also consider numerous sections of the Shī`ī Arabic Rawḍat al-kāfī (The Garden of Sufficiency) volumes supplementary to the Uṣūl al-kāfī of Abu Ja'far Muhammad b. Ishāq Kulaynī (d. c.328 /940).

Islamic pseudepigraphical texts include thousands of sayings or writings ascribed, for example, to

- Adam, viewed as the first man and a prophet married to Eve.

- Enoch-Idrīs. Note the qur’anic mentioned for some originally Syriac (pl.) ṣuḥuf (sing. saḥīfa) or biblically influenced (Gen. 1:1ff; 2:10ff) scriptural leaves attributed to Enoch-Idrīs. Many are paraphrased and set out in the Sa`d al-su`ūd li’l-nufūs manḍūd (The Felicity of Good Fortune for Blanketed Souls”) of Ibn Tawūs (d. 664/1226) and registered in the Biḥar al-anwār (Oceans of Lights) of Muhammad Baqir Majlisī (d. 1111/1699-1700) which cites no less than twenty-nine titled, pre-Islamic pericopes ascribed to Idrīs-Enoch and related sources (Bihar, 2nd ed. vol. 95: 453- 472; cf. 11: 269).

- Noah

- Abraham

- Moses

- David,

- Ezekiel

- Daniel

- and others.

David and the Zabūr or Mazamir (Book of Psalms or Psalter).

Islamicate recreations or versions of the Zabūr or Mazamir (Book of Psalms) and the Book of Daniel such as the Kitāb al‑malāḥim li Dāniyāl (The Book of the Conflagration of Daniel) exist in a number of Shī`ī recensions, including one with an introduction by Majlisī’s pupil Ni`mat‑Allāh al‑Jazā’irī (d. 1112/1701) and transmitted by Ibn Ṭāwūs. [3]

Extra-qur’ānic “divine sayings” or ḥadīth qudsī attributed to biblical figures as transmitted by the Prophet Muhammad or the Shī`ī Imams. These include a great deal of Islamo-biblical material, even whole pseudepigraphical books. According to some traditions the Prophet and the Imams were heir to pure forms of pre-Islamic sacred writ either orally or through secreted and guarded channels. The well-known Sufi theological disclosure which commences, “I [God] was a hidden treasure” (kuntu kanzan makhfiyan) believed to have been revealed to the biblical-qur’anic David. This exists a quite lengthy Arabic supplication containg a prophetological prayer attributed to his mother (umm Dāwūd) which includes the lines :

O my God! Blessings be upon [1] Hābīl (Abel), [2] Shīth (Seth), [3] Idrīs (Enoch), [4] Nūḥ (Noah), [5] Hūd [6 ] Ṣalīḥ [7] Ibrāhīm (Abraham), [8] Ismā’īl (Ishmael) and [9] Isḥāq (Isaac) [10] Ya`qūb ( Jacob), [11] Yūsuf (Joseph), [12] and the tribes [of Israel] (al-asbāt) [13] Lūṭ (Lot), [14] Shu`ayb, [15] `Ayyūb (Job), [16] Mūsā (Moses), [17] Hārūn (Aaron), [18] Joshua, [19] Mīshā (Mūshā) Moses [ibn Manasseh], [20] Khiḍr, [21] Dhū‑l-Qarnayn ("Alexander th Great”) [22] Yūnūs (Jonah), [23] llyas (Elijah), [24] Iyasu` (Elias), [25] Dhu'l-Kifl, [26] Tālūṭ (XXXX), [27] Dā’wūd (David), [28] Sulaymān (Solomon), [29] Zakā’riyya (Zachariah), [30] Yaḥyā (John [the Baptist]), [31] T-W-R-KH (Torakh = Turk?) [32] Mattā (Matthew), [33] Irmīyā (Jeremiah) [34] Hayaqoq (Habbakuk), [35] Danyāl (Daniel) [36] `Azīz ("Mighty") [37] `Īsā’ (Jesus), [38] Shimūn (Simon), [39] Jirjīs (St. George) [40] the Apostles [of Jesus] (al-ḥawarīyyun), [41] the successors' [`Followers' of Jesus?] (al-/ffibã`), [42] Khalid [b Sinan]), [43] Hanzalah and [44] Luqman“ (cited Majlisī, Biḥār 2 11:59).

It will be observed that this lengthy prophetological beatitude lists over forty messengers and related figures in a loose and sometimes eccentric chronological order. Islamic devotion to the Israelite and related prophets, largely unmentioned in the Qur’ān, would seem to be implied here. This prophetological paragraph is among very many Islamic devotional pieces which are attributed to pre‑Islamic figures in Shī`ī devotional and related compilatiions.

Works in the category of Islamic pseudepigraphon were considered important enough to be ascribed to such past sages and prophet figures including Adam, Enoch, Hermes, Moses, Solomon, Daniel, Jesus and others. Examples include a proto-qur’anic Munājāt Mūsā (“Supplications of Moses”), Islamic recreations of the Zabūr of David sometimes reflectring the biblical Psalms (Schippers, `Psalms’ Enc.Q 4:314-8) and even an Islamic Tawrāt (“Torah”) divided, like the Qur’ān, into sūrahs! These Islamo-biblical recreations with the many texts in Islamic sources ascribed to pre-Islamic scripture are worthy of serious scholarly attention. They can be viewed as the fruits of a creative scriptural symbiosis among diverse “people of the Book” and should not be dismissively or derisively ignored as merely pseudo-biblical phenomenon.

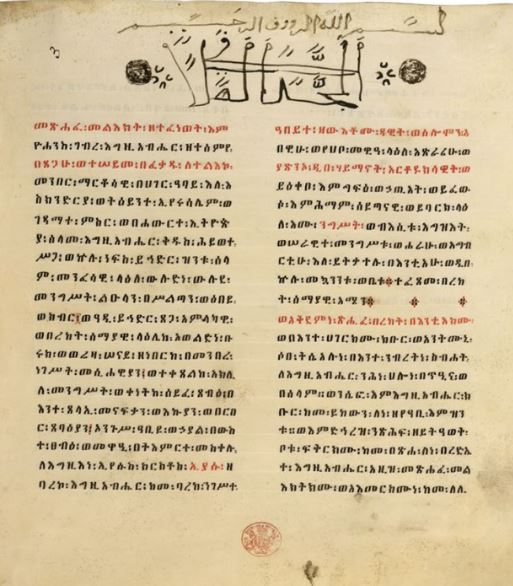

Though genuine manuscripts representative of the early Arabic bible translation are few, Islamic pseudepigraphical texts and writings are numerous. Some Muslims claim to have rediscovered or creatively invented allegedly "genuine" texts or portions of the Tawrāt (Pentateuch) of Moses, the Zabūr ("Psalter") of David, the original injīl (Gospel) of Jesus as well as and other books ascribed to pre‑Islamic prophets such as David. A modern example is the so-called “Gospel of Barnabas”.

[1] The Pseudepigrapha are not simply (“pseudo-writings”) but highly valued non-canonical Jewish or Christian (or other) texts ascribed to biblical worthies. A pseudepigraphon is a pseudonymous work of this kind.

[2] By neo-biblical I mean Islamo-biblical texts or books claiming to be biblical but transcending in form or content Jewish and/ or Christian Biblical scripture and related texts. .

[3] Shī`ī tradition has it that knowledge of the cryptic predictions in the Malḥamat Dāniyāl induced the Sunnī Caliphs Abū Bakr and `Umar to gain successorship after the passing of Muhammad (Fodor 1974:85ff; Kohlberg 1992:143).

EARLY VERSION

Islamic pseudepigraphical texts and biblically ascribed writings.

Islamic pseudepigraphical texts and writings may have biblical-qur’ānic ascription but often exhibit little or no concrete biblical basis or substrate. [1] = The Pseudepigrapha are not simply (“pseudo-writings”) but highly valued non-canonical Jewish or Christian (or other) texts ascribed to biblical worthies. A pseudepigraphon is a pseudonymous work of this kind. Certain citations Included here might be labeled neo-biblical [2] or proto-qur’ānic in that they are Islamic creations modeled on and reflecting the form and / or content of the Qur’ān. By neo-biblical here I mean Islamo-biblical texts or books claiming to be biblical but transcending in form or content Jewish and/ or Christian Biblical scripture and related texts. Many sayings ascribed to biblical figures are found in Islamic sources as are Islamic versions of biblical books and pericopes. This is illustrated in many ḥadīth qudsī traditions such as are found in ḥadīth Arba`ūn (Forty Hadīth) compilations and sections, for example, of the Shī`ī Rawḍat al-kāfī (The Garden of Sufficiency) volumes supplementary to the Uṣūl al-kāfī of Abu Ja'far Muhamad b. Ishāq Kulaynī (d. c.328 /940).

Examples of this category of texts include,

- Pseudepigraphical texts ascribed to Adam, Abraham Moses David, Daniel and others including, for example, the allegedly originally Syriac (pl.) ṣuḥuf (sing. saḥīfa ) or biblically influenced (Gen. 1:1ff; 2:10ff) scriptural leaves attributed to Idrīs-Enoch as paraphrased and set out in the Sa`d al-su`ūd li’l-nufūs manḍūd (The Felicity of Good Fortune for Blanketed Souls”) of Ibn Tawūs (d. 664/1226) and such other writings as the Biḥar al-anwār (Oceans of Lights) of Muhammad Baqir Majlisī (d. 1111/1699-1700) which cites no less than twenty-nine titled, pre-Islamic pericopes ascribed to Idrīs-Enoch and related sources (Bihar, 2nd ed. vol. 95: 453- 472; cf. 11: 269).

- Islamicate recreations or versions of the Zabūr or Mazamir (Book of Psalms) and the Book of Daniel such as the Kitāb al‑malāḥim li Dāniyāl (The Book of the Conflagration of Daniel) existing in a number of Shī`ī recensions including one with an introduction by Majlisī’s pupil Ni`mat‑Allāh al‑Jazā’irī (d. 1112/1701) and transmitted by Ibn Ṭāwūs. [3] Shī`ī tradition has it that knowledge of the cryptic predictions in the Malḥamat Dāniyāl induced the Sunnī Caliphs Abū Bakr and `Umar to gain successorship after the passing of Muhammad (Fodor 1974:85ff; Kohlberg 1992:143).

- Extra-qur’ānic “divine sayings” or ḥadīth qudsī attributed to biblical figures as transmitted by the Prophet Muhammad or the Shī`ī Imams. These include a great deal of Islamo-biblical material, even whole pseudepigraphical books. According to some traditions the Prophet and the Imams were heir to pure forms of pre-Islamic sacred writ either orally or through secreted and guarded channels. The well-known Sufi theological disclosure which commences, “I [God] was a hidden treasure” (kuntu kanzan makhfiyan) believed to have been revealed to the biblical-qur’anic David and a prophetological prayer attributed to his mother (umm Dāwūd) (see below):

O my God! Blessings be upon [1] Hābīl (Abel), [2] Shīth (Seth), [3] Idrīs (Enoch), [4] Nūḥ (Noah), [5] Hūd [6 ] Ṣalīḥ [7] Ibrāhīm (Abraham), [8] Ismā’īl (Ishmael) and [9] Isḥāq (Isaac) [10] Ya`qūb ( Jacob), [11] Yūsuf (Joseph), [12] and the tribes [of Israel] (al-asbāt) [13] Lūṭ (Lot), [14] Shu`ayb, [15] `Ayyūb (Job), [16] Mūsā (Moses), [17] Hārūn (Aaron), [18] Joshua, [19] Mīshā (Mūshā) [2nd] Moses, son of Manasseh), [20] Khiḍr, [21] Dhū‑l-Qarnayn ("Alexander the Great”+) [22] Yūnūs (Jonah), [23] llyās (Elijah), [24] Iyasu` [al-Yasa` b. Akhṭūb] (Elias), [25] Dhu'l-Kifl, [26] Tālūṭ (Goliath), [27] Dā’wūd (David), [28] Sulaymān (Solomon), [29] Zakā’riyya (Zachariah), [30] Yaḥyā (John [the Baptist]), [31] T-W-R-KH (Torakh = Turk?) [32] Mattā (Matthew), [33] Irmīyā (Jeremiah) [34] Hayaqoq (Habbakuk), [35] Danyāl (Daniel ) [36] `Azīz ("Mighty") [37] `Īsā’ (Jesus), [38] Shimūn (Simon), [39] Jirjīs (St. George) [40] the Apostles [of Jesus] (al-ḥawarīyyīn), [41] the successors' [`Followers' of Jesus?] (al-/ffibã`), [42] Khalid [b Sinan]), [43] Hanzalah and [44] Luqman “ (Majlisī, Biḥār 2 11:59).

This prophtological supplication is among very many devotional pieces which are attributed to pre‑Islamic figures in Shī`ī devotional and related compilatiions. It will be seen that this lengthy prophetological beatitude listis over forty messengers and related figures in a loose and sometimes eccentric chronological order. Islamic devotion to the Israelite and related prophets, largely unmentionedin the Qur’ān, would seem to be implied here.

These apologetic and interpretive Islamo-biblical citations echo Jewish Aramaic Targumic renderings which translate and make the Biblical Hebrew text meaningful for succeeding generations. Islamo-biblical and neo-biblical texts are no more “false” than Christian generated pseudepigraphal writings, recreations and re-translations of texts within the, Hebrew Bible and Jewish tradition.

Works in the category of Islamic pseudepigraphon were considered important enough to be ascribed to such past sages and prophet figures including Adam, Enoch, Hermes, Moses, Solomon, Daniel, Jesus and others. Examples include a proto-qur’anic Munājāt Mūsā (“Supplications of Moses”), Islamic recreations of the Zabūr of David sometimes reflectring the biblical Psalms (Schippers, `Psalms’ EQ 4:314-8) and even an Islamic Tawrāt (“Torah”) divided, like the Qur’ān, into sūrahs! These Islamo-biblical recreations with the many texts in Islamic sources ascribed to pre-Islamic scripture are worthy of serious scholarly attention. They can be viewed as the fruits of a creative scriptural symbiosis among diverse “people of the Book” and should not be dismissively or derisively ignored as merely pseudo-biblical phenomenon.

Though genuine manuscripts representative of the early Arabic bible translation are few, Islamic pseudepigraphical texts and writings are numerous. Some Muslims claim to have rediscovered or creatively invented allegedly "genuine" texts or portions of the Tawrāt (Pentateuch) of Moses, the Zabūr ("Psalter") of David, the original injīl (Gospel) of Jesus as well as and other books ascribed to pre‑Islamic prophets such as David. A modern example is the so-called “Gospel of Barnabas”.

■ The “Gospel of Barnabas”

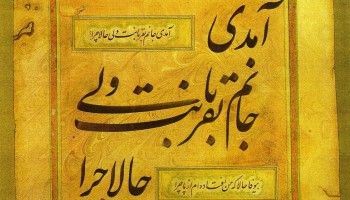

The 222 chapter (200+ pages) “Gospel of Barnabas” ascribed to a Christian companion of Paul originally named Joses then Barnabas (fl. 1st cent CE., Acts 4:36, Chs. 11-15), might be mentioned here since it is essentially a 16th century CE Islamic created Gospel harmony extant in only a few 16-17th mss. of Spanish and Italian Morisco (Crypto-Muslim) provenance. Without any ancient mss. basis It has been frequently reprinted and translated in the Muslim world (Arabic, 1908; Urdu, 1916 etc) from the 1907 English translation (from an Italian MS. in the Imperial Library at Vienna) of Lonsdale and Laura Ragg though without their critical introduction in which it was exposed as a medieval `forgery’.

Within its text Muhammad is mentioned by name and many Muslims today view this `Gospel of Barnabas’ as the only remaining authentic Gospel despite the fact that western scholarship has for long remained unconvinced of its veracity (Ragg, 1907; Sox, 1984; Slomp, URL). A massive literature now surrounds the debate over this and related issues of scriptural preservation, transmission, falsification and veracity. Abrahamic religionists have long accused each other of tampering with sacred writ and of misquoting established scripture to suit selfish or polemical purposes

[1] The Pseudepigrapha are not simply (“pseudo-writings”) but highly valued non-canonical Jewish or Christian (or other) texts ascribed to biblical worthies. A pseudepigraphon is a pseudonymous work of this kind.

[2] By neo-biblical I mean Islamo-biblical texts or books claiming to be biblical but transcending in form or content Jewish and/ or Christian Biblical scripture and related texts.

[3] Shī`ī tradition has it that knowledge of the cryptic predictions in the Malḥamat Dāniyāl induced the Sunnī Caliphs Abū Bakr and `Umar to gain successorship after the passing of Muhammad (Fodor 1974:85ff; Kohlberg 1992:143).