A Tablet of Bahā'-Allāh to Georg David Hardegg, the Lawḥ-i Hartīk 1

═══════════════════════════════════════════════

Stephen N. Lambden 1983.

With additions and revisions November 2004 + 2015 (in progress).

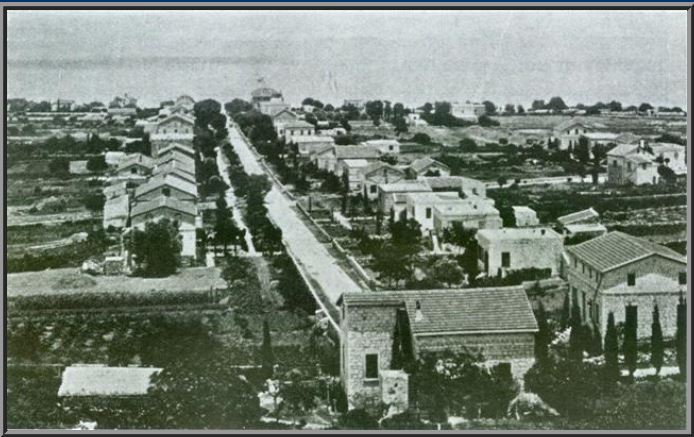

Georg David Hardegg The Templar Colony, 1893.

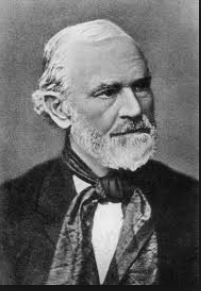

Georg David Hardegg (1812-1879)

Mīrzā Ḥusayn `Alī Nūrī Bahā’-Allāh (1817-1892) addressed a number of letters or scriptural tablets (alwaḥ) to Christians during the latest, West Galilean (loosely, `Akkā' = Acre) period of his religious ministry (1868‑1892 CE). Most notably his Lawḥ-i Pāp (Tablet to Pope Pius IXth. c.1869) and the Lawḥ-i aqdas (Most Holy Tablet, late 1870s?) which was most probably addressed to Fāris Effendi who had been converted to the Bahā'ī religion by Mullā Muhammad Nabīl-I Zarandī (c. l831-1892) in Alexandria in 1868. It is now clear that the letter of Bahā’-Allāh commonly refered to as the Lawḥ-i Hirtīk (more accurately Hartīk = Hardegg) was also addressed to a Christian named Georg David Hardegg (1812-1879). During the time of Bahā’-Allāh’s imprisonment in `Akkā', Hardegg was the leader of the Tempelgesellschaft (Association of Templers [alternatively,`Templars']) community in Haifa.

On first coming to know something of the nature of the Lawḥ‑i Hirtīk through the note on this Tablet in `Abd al-Ḥamīd Ishrāq Khāvarī's Ganj-i shāyigān, 2 (and since it had not been published), I wrote to the Bahā'ī World Centre in Haifa requesting a copy for detailed study. On receipt of a typed copy (cf. text below) I began to try to work out what the consonants H‑R‑T‑K might signify, as they were evidently neither indicative of an Arabic nor a Persian construction. Ignoring the pointing and guessing that it might indicate the name of the recipient of the letter, the name Hardegg eventually sprang to mind. I then consulted Moojan Momen's The Bābī and Bahā'ī Religions and was delighted to find that what was obviously a very garbled translation of the Lawḥ-i Hirtīk had been forwarded by the missionary Rev. John Zeller (c.1830-1902) to the English Church Missionary Society and identified as a letter of Bahā’-Allāh to Hardegg 3 Furthermore, as Zeller's letter forwarding Bahā’-Allāh’s Lawḥ-i Hirtīk was dated July 8 1872 it may be inferred that the Lawḥ-i Hirtīk was written between late 1868 (when both Bahā’-Allāh and Hardegg arrived in `Akkā' and Haifa respectively) and 8th July 1872. It was thus most probably between late 1871 and early 1872 (=1288-1289 AH) that Bahā’-Allāh addressed this Tablet to the Templer leader.

∎ Hardegg and the Tempelgesellschaft

The Tempelgesellschaft was founded by the German theologian and polemicist Christoph Hoffmann (b. Leonberg 1815 d. Jerusalem 1885) whose religious orientation was rooted in German Pietism of an highly chiliastic nature. Influenced by the belief that God's judgement and the parousia of Christ were at hand, and critical of the "conventional Christianity" of his day, he came, while residing in Ludwigsberg in the early 1850's, to advocate the creation of das Volk Gottes (the "people of God"). He was apparently influenced either by events of the Crimean War (1853-6) or the belief that the Ottoman Empire was crumbling in such a way that he conceived the idea that he and his people might become heirs to the Biblical promises. He elaborated a theory centering upon the [Jerusalem] Temple and its restoration, and dreamed of a mass emigration to Palestine.

In 1854 such visionary ideas led Hoffmann to establish the Gesellschaft für Sammlung des Volkes Gottes in Jerusalem (The Association for the Assembling of God's People in Jerusalem). In this he was aided by his associate Georg David Hardegg, a native and merchant of Ludwigsberg, who had turned to mysticism after being imprisoned for revolutionary activities. By the mid‑1850s Hoffmann and Hardegg had managed to enlist around 10,000 members.

An attempt was made via the Frankfurt Assembly to petition Sultan `Abd al-Majīd (Ottoman Sultan from 1839‑1861) for permission to settle in Palestine. This petition failed and the members of the association had to content themselves with the establishment of a settlement near Marbach (1856). Four of the leaders of the movement, including Hoffmann and Hardegg, visited Palestine in 1858. To some extent they came to realize the largely impractical nature of their eschatologically oriented ambitions. Then, in 1859, the leaders of "God's people" were formally expelled from the National Evangelical Church. Consequently, in 1861, they set up their own distinctive religious body at Kirschenhardhof, the Deutsche Tempel. Hoffmann acted as spiritual leader and Hardegg as provisional secular leader, with an advisory council of 12 elders.

By1867 numbers had dwindled to just 3,000, including women and children. Despite this in 1868 a group of Templer families made an abortive attempt to settle in the Nahalal area of Northern Palestine. Though by this time a bitter antagonism had come to exist between Hoffmann and Hardegg, it was decided to emigrate to Palestine and attempt to gain support for the movement from there. Thus, both Hoffmann and Hardegg arrived at Haifa on the 30th of October 1868. They began establishing amidst considerable local opposition and difficulty, an initially agricultural settlement. A few dozen Templer families from Württemberg (S. Germany) settled at the foot of the western cape of Mt. Carmel. According to Katz they were "joined by kindred families of German origin from southern Russia, and by some who had emigrated to America and become citizens, mainly from New York state" (Katz 1994:263).

In 1869 Hoffmann migrated to Jaffa where he came to establish a school and a hospital 4 By 1874 the breach between Hoffmann and Hardegg was such that the latter founded his own Temple Unity having gained the support of about one third of the perhaps 200 (?) members of the Haifa community. These supporters of Hardegg subsequently returned to the (German) Evangelistic Church, though the Haifa Templers under new leadership continued to prosper. They contributed notably to the modernization and improvement of local Haifa conditions. Despite sometimes marked local opposition from Muslims and Christian Arabs, the number of Haifa Templers rose from about 300 in the early 1880s to around 750 at the time of the outbreak of the First World War (1914) 5

Among the letters contained in J. M. Emmerson’s 1887 travelogue entitled New York to the Orient is one that includes details about local circumstances in Haifa and Acre including the position of the "German Colony" (= Templars):

One of tile most noteworthy and interesting features of Haifa is the settlement here of group of Germans, known as the German Colony. They came here some twenty ‑ five years ago, being prompted to emigrate thither by a religious sentiment. There are three distinct colonies of them in Palestine – at Jerusalem, Jaffa, and Haifa– consisting of about one thousand members. The colony here [at Haifa] numbers some three hundred persons, and they are in many respects a remarkable people. The appearance of the part of the city they occupy is in striking contrast with the main town in that it is regularly laid out, and is clean and orderly. These colonists are the only people who have ever come to live in Palestine who are self‑supporting... (Emmerson 1887:113).6.

SCANS OF TEMPLAR COLONY

∎ Hardegg and the Bahā'ī religion

Hardegg most likely made other trips to Acre (`Akkā') in order to investigate Bahā'ī beliefs and attempt to interest or convert the Bahā'īs to Christianity. The missionary James J. Huber (1826-1893) who resided at Nazareth during the 1870s has recorded in a letter dated November 28 1872 that Hardegg had invited him to accompany him on a visit to the Acre (`Akkā') Bahā'īs. They travelled together to Acre (`Akkā') in October 1872 having been promised an interview with Bahā’-Allāh by some of the Bahā'īs. Perhaps as a result of Bahā’-Allāh's withdrawal in the house of `Ūdī Khammār following Bahā'ī‑Azalī tensions and the misdeeds of certain Bahā'īs which culminated in the murder of several AzaIīs 7 the interview with Bahā’-Allāh did not materialise. Instead Hardegg and Huber conversed with `Abdu’l-Bahā' (Momen, op.cit., 218).

Hardegg's desire to gain an interview with Bahā’-Allāh has been referred to by Bahā’-Allāh himself in a scriptural Tablet (lawḥ) which was written around 1875 and addressed to Ḥājjī Mīrzā ḥaydar `Alī Isfahānī (d. Haifa 1920) (? cf. Ganj, 172‑3). In it Bahā’-Allāh stated that all the [Holy] Books "make mention of the appearance of the Promised One in the Holy Land". He alludes to the Templers who came from afar to settle in the regions of the blessed Holy Land. Calling to mind the well-known German Templer inscription Der Herr ist nahe [1871]", meaning, "God is nigh" (cf. Ruhe, op. cit. 193n) the Templers are represented as having said ẓuhūr nazdīk ast,

"The theophany [manifestation] is nigh and we have come that we might attain unto it (his presence)."

Nevertheless, Bahā’-Allāh adds, they remain in great heedlessness. None of the Templers had become Bahā'īs. Reference is then made to Hardegg and to the writing or revelation of the Lawḥ-i Hirtīk:

"A few years ago their leader [Hardegg] desired to attain [my] presence but this request did not find acceptance in the most-holy court. Nonetheless, a sublime and most-holy Tablet (lawḥ‑i amna`‑i aqdas) was specifically sent down for him. In that Tablet was established that which enableth every righteous one to attain salvation and every wayfarer to reach the goal. Yet the confirmation of the utterance, "Let none touch it save those who are pure" was manifest for they did not attain even a drop of the ocean of its significances..." (Text cited Ganj, 172‑3)

Though Bahā’-Allāh represents the 19th century Templers as a people who failed to understand or respond to his message, the Bahā'īs seem to have had cordial relations with them. Bahā’-Allāh himself, on several occasions, perhaps had personal contact with them in the course of his several trips to Haifa during the 1880s and early 1890s.

Footnotes

2. Refer, Ganj, 172-3. Here Ishrāq Khāvarī mistakenly identifies the followers of the recipient of the Lawh-I Hirtīk with the Millerites or followers of William Miller (1782‑1849 CE).

3. Refer Momen, The Bābī and Bahā'ī Religions. 216-8.

4. In 1871 Hardegg’s son Ernst became US consular agent in Jaffa. There he remained in office until 1909 when he resigned at the age of seventy (Kark, 1994:114).

5. On the Tempelgesellschaft refer to the entries in the bibliography below and, Whitley, `Friends of the Temple' ERE 6:141-2; Kolb, `Friends of the Temple'; Ussishkin, `Templers (Tempelgesellschaft)' Enc. Judaica’ 15:994-996 (this article is especially useful for details on 20th century Templer history); Alex Carmel, Die Siedlungen .. ; idem,`The German Settlers in Palestine...’ 442-465; cf. also Oliphant, Haifa or Life in Modern Palestine, 17ff; Momen, The Bābī and Bahā ’ī religions 215f, 503, 506f, 521. For some useful information on contacts between Bahā'īs and Templers see Ruhe, Door of Hope, 1982, index.

6. A recent booklet put out by the Haifa Tourist Board entitled, `Baha’i Shrine and Gardens on Mount Carmel, Haifa-Israel` contains two pages which illustrate the Haifa project, “the restoration and development of the main axis of the German Templar Colony”. This small booklet ADD HERE

7. The AzaIīs are the followers of Bahā’-Allāh's younger half-brother Mīrzā Yaḥyā (c.1830‑1914) who was entitled Subh‑i Azal (The Morn of Eternity) and had been exiled from Ottoman Turkey to Cyprus in 1868.