Some Notes on the Abrahamic-Islamic pre-history and intertextuality of Traditions about the Person and Name آسية (Ar.) Āsiya (Per. Āsiyih), the Name of the wife of Bahā’-Allāh (1817-1892) and the Mother of `Abdu’l-Bahā’ `Abbās (1844-1921).

Stephen Lambden UC Merced, 1980s revised 2020.

In Progress - last updated 14-09-2020.

The name often spelled in Arabic or Persian آسية = Āsiya [e-ih] has been variously and somewhat confusedly transliterated, e.g. Āsiyah, Āsīya, Asiyyah, Asiyih, Aseyeh etc. There exist many variant forms, spellings and transliterations originating in a variety of ancient Semitic and other languages. In these notes I shall use the Arabic tranliteration Āsiya unless context, citation or other factors demand otherwise. Forms of this name have been variously thought over the last two millennia and more, to be the name of the wife or daughter of Pharoah, the wife of Joseph and more recently the name of the wife of Baha’u’llah (1817-1892) - founder of the Baha;'i religion- and the mother of his son and successor `Abdu’l-Baha’ `Abbas(1844-1921). The paragraphs below will attempt to sum up a few aspects of the often legendary history of the female person or persons who bore this or a similar name. It is a name with a very interesting history or prehistory within the Abrahamic religions, namely and primarily, Israelite religion-Judaism(s), Christianity and Islam with its vast religious literatures of exegesis, poetry, philosophy and mysticism.

Post-biblical Jewish writings dating after the Babylonian exile of the Jews in the 6th century BCE., as well as later post 7th cent. CE Islamic legends, have it that more than three thousand years ago an outstandingly pious and religious woman bore the name Āsiya. She allegedly lived in Egypt and is reckoned to have been the wife of Joseph or, among other things, a courageous and saintly female contemporary of Moses.

In Hebrew, Greek and other languages, the variant spellings of the name Āsiya have, among others, the following spellings and meanings (again the transliterations vary):

-

אָסְנַת Hebrew rooted in Ancient Egyptian as Asenath, the wife of Joseph and the mother of his sons, Manasseh and Ephraim (Gen 41:50, 46:20), the names of two of the tribes of Israel. It probably derives from a form of the Egyptian meaning "possession of the goddess Neith” (“nt > Nit) resulting in ʼāsənạṯ[th] loosely, 'asenath” meaning “holy to [the Egyptian goddess] Anath".

- Y

- Y

- Y

- Y

Āsiyya or (Heb.) Āsina, (Greek) Asenath is in many Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyā’ (Stories of the Prophets) and related Islamic literatures and their pre-Islamic Jewish, Christian and other sources, reckoned to have been a contemporary of Moses (fl. between c. 1200-1600 BCE – biblical and other datings vary greatly).

"The Arab lexicographers derive Āsiya's name from the verb asā (from which, by pseudo‑etymology, Mūsā, "Moses," may also be derived), meaning "healing" and "solace" (cf. the Syriac asiya, "physician"), which latter function she performs with respect to both Moses and Pharaoh. The possibility of Mūsā as "source/instrument of healing" was recognized and employed in the legend when, as a babe, his presence heals the diseased daughters of Pharaoh." (Thackston, 252 fn.100). cf. Essenes.

The Israelite heroine Asenath (Egyptian `belonging to/ servant of [the female God] Neith' (fl.c. 1400 BCE), was the daughter of Potiphera (Pentephres) priest of On (= Heliopolis, Egypt). She was given by Pharoah to Joseph as a wife and became the mother of Ephraim and Manasseh (Gen 41:45ff; 46:20).

Asenath (loosely = Āsiya) has been variously identified in Jeish and Christian sources. It has been noted that post-Biblical "Jewish legends attempted to explain the apparent heathen origin of Joseph's wife. In one recension she is pictured as a Hebrew (daughter of Schehem and Dinah) who was adopted by Potiphera; elsewhere it is claimed that although she was Egyptian, she was converted to Yahwism by Joseph." (J.F. Ross, Asenath, IBD I:247-8; cf. Ginsberg Legends II (1910), 38, 170ff)

It has been observed by Walker that the name Āsiya in Islamic sources corresponds to the Biblical Hebrew Asenath (Walker, 1928) -- scribal error (pointing misplacement) "N" ->" Y"?). It has been further observed however, that "there is little justification for this interpretation since Āsiya is, in all sources, named as the daughter of Muzāhim and has no connection whatsoever with Joseph, in whose legend the roles of both Asenath and of the wife of Potiphar have been combined in the figure of Zuleikha" (Thackston, 1978:351).

The Note on Āsiya by Wheeler Thackston, retired Professor of the Practice in Persian and Other Near Eastern Languages at Harvard University.

Thackston further observes in his translation of the 11th cent CE., Qisas al-anbiya (Stories of the Prophets) of al-Kisa'i (G.K. Hall & Co. 1978) pp.351-2 (fn. 100) :

"It has been suggested (Walker, "Asiya," 48) that Āsiya is a scribal error for Āsina (= Asenath, the daughter of Poti‑pherah and wife of Joseph, see Gen 41:45, 41:50 and 46:20), although there is little justification for this interpretation since Āsiya is in all sources named as the daughter of Muzāḥim and has no connection whatsoever with Joseph, in whose legend the roles of both Asenath and of the wife of Potiphar have been combined in the figure of Zuleikha. Walker connects Āsiya's legend, especially her martyrdom at the hand of Pharaoh, with that of St. Catherine of Alexandria, who shares a number of attributes with Āsiya, including a connection with Moses in that Catherine's supposed tomb is at Jebel Ekaterina in Sinai near the Jebel Musa, where the Decalogue is said to have been revealed. St. Catherine was of royal lineage; Ibn Kathlr (Qisas al‑anbiya', II, 8) gives Āsiya's name as Asiya bint Muzāḥim ibn [p.352 Tales of the Prophets of al‑Kisa'i] 'Ubayd ibn al‑Rayyān ibn al‑Walīd, thus establishing her to be of royal lineage also. Of striking similarity to Pharaoh's torture of Āsiya is the account of the martyrdom of St. Catherine: Āsiya is tortured to death with iron stakes, after which the angels bear her off into heaven in a dome of light (see Nlsaburi, Qisas al‑anbiya', p. 187), a standard topos in martyrologies, cf. the old woman put to death by Nimrod (p. 141 above) and the martyrdom of Queen Alexandra in the St. George legend (Tha'labi, Qisas, p. 392 and also in the Syriac version in Acta martyrum et sanctorum, ed. Bedjan, I, 295ff.). Āsiya's last words are given in Koran 66:11: "Lord, build me a house with thee in paradise; and deliver me from Pharaoh and his doings, and deliver me from the unjust people."

As Āsiya is Pharaoh's wife and not his daughter (called Thermutis in Midrashic literature ), she is placed in relation to Haman the Vizier as was Esther, from whose legend Haman (chief minister to Ahasuerus) was lifted. There may possibly be some connection between Esther's name, Haddasah ("myrtle"), and the Arabic ās (also "myrtle") and Āsiya. The Arab lexicographers derive Āsiya's name from the verb asā (from which, by pseudo‑etymology, Mūsā, "Moses," may also be derived), meaning "healing" and "solace" (cf. the Syriac āsiyā, "physician"), which latter function she performs with respect to both Moses and Pharaoh. The possibility of Musa as "source/instrument of healing" was recognized and employed in the legend when, as a babe, his presence heals the diseased daughters of Pharaoh.

There are some unmistakably alchemical elements in the Moses legend, particularly the "nonburning" of the Moses‑infant amidst the raging fire (this has its parallel too in the Abraham legend) and the subsequent casting of the child into the waters for a certain period of time ( all of the variant lengths of time recorded would be of significance), after which the infant effects miraculous cures. The connection of Moses with alchemy is carried further in his relation to Korah (see p. 245). Moses is known to figure prominently in the alchemical literature of late antiquity and in the Greco‑Arabic tradition also (see E. J. Holmyard, ed., The Arabic Works of Jabir ibn Hayyan, I, p. 86).

The notes on the following pages below are to some degree inspited by these learned though now dated observations of Thackston and similar researches of modern scholars of the Abrahamic religions. Attention will also be given to Islamic Tafsir, Hadith and Qisas al-anbiya literatures as well as the few relevant Baha'i scriptural texts.

Select works of interest within the so-called `Joseph Cycle'.

The History of Joseph and Asenath (2nd cent. BCE?).

Originally in Greek though there are several translations or versions in Syriac, Armenian, Slavonic and other languages. The Greek original text has been several times reconstructed.

The `[History of] Joseph and Asenath' an haggadic midrash/Hellenistic romance on Gen 41:45 ("and he [Pharoah] gave him [Joseph] in marriage Asenath, the daughter of Potiphera priest of On". This work in twenty-nine chapters was probably originally written in Greek in pre-Christian Jewish circles though it was most likely several times later redacted by Christians. The original dating of this history as well as the dating of its later recensions spans several centuries, perhaps 1st cent BCE up till the 6th Cent CE (see Sparks, 1984:465ff)

- 2) Book of the Prayer of Asenath.

- 3) Life and Confession of Asenath.

- 4) History of Assaneth.

(See Charlesworth, 1981:137ff).

The Rabbinical Asenah

Aptowitzer, Victor. “Asenath, the Wife of Joseph. A Haggadic Literary-Historical Study.” Hebrew Union College Annual vol. 1 (1924), 239–306.

Tamar Kadari, `Asenath: Midrash and Aggadah' see :

Āsiya in the Qur'an, Hadith and other Islamic sources

Extant legends about Asenath have contributed to the Islamic traditions about Āsiya. She figures -- though she is often not explicitly identified or named in the Qur'ān and in many Islamic qisas al-anbiyā' ("stories of the prophets") literatures. The Islamic Āsiya is believed to be the "daughter of Mu`azhim and wife of Pharoah" who said of Moses "He will be a comfort to me and thee. Slay him not; perchance he will profit us, or we will take him for a son." (Q 28:00). In Qur'ān 66:11 she is an object lesson for the believer:

"God has struck a similitude for the unbelievers -- the wife of Pharoah, when she said, `My Lord, build for me a house in Paradise, in Thy presence, and deliver me from Pharoah and his work, and do thou deliver me from the people of the evildoers." (trans. Arberry, 594-5)

In many Islamic sources Āsiya -- daughter of Muzāhim (ibn `Ubayd ibn al-Rayyān ibn al-Walād) -- is identified as the "wife of Pharoah"’ Thus, in the following Sunni tradition related by Bukhāri and Muslim;

"Abā Mūsā reported the Prophet saying, "Many men have been perfect, but among women only Mary the daughter of `Imrān and Āsiya the wife of Pharoah were perfect.." (cited, Mishkat II:1225)

In legend Āsiya is said by al-Kisa'i to have been conceived on the very night that Āsiya's father married; a night which corresponded with the day that Joseph married Zuleikha (al-Kisa'i, trans. Thackston, 213-4).

"When Asiya had reached her twentieth year, a white bird in the form of a dove appearecl to her with a white pearl in its mouth.

"Asiya," it said, "take this white pearl, for when it turns green it will be time for you to marry; when it turns red God will cause you to suffer martyrdom." Then the bird flew away. Asiya took the pearl and fastened it to her necklace.

When Pharaoh heard of her beauty, he wanted to marry her and sent to her father Muzahim to dispatch his daughter. When Muzahim told Asiya the news, she wept bitterly and said, "How can a woman who believes be the wife of an infidel?"

"My daughter," he said, "you are right; but if I do not do as he says, he will destroy us and all our people." Therefore she complied with his wish.

As a bride‑price the king gave her thousands of okes of gold and ordered so many thousands of sheep slaughtered that there was not a soul in Egypt who was not invited to partake of the feast he had prepared.

When she entered under his roof, Pharaoh came in intent upon her; however, God kept him from her and made him impotent. Then he heard a voice saying, "Woe unto you, O Pharaoh! Verily the end of your kingdom draws nigh at the hand of a man from the children of Israel called Moses."

"Who is that talking?" asked Pharaoh.

"I do not know," answered Āsiya." (al-Kisa'i, trans. Thackston, 214)

"Pharaoh had seven daughters, not one of whom was free of disease. As treatment the physicians had advised them to bathe in the water of the Nile, so Pharaoh had a large pool con‑structed in his house, and filled it with Nile water. God commanded the breeze to carry the ark and leave it in that stream. The eldest daughter discovered the ark, opened it and saw Moses inside, shining with the brilliance of the sun. When she took him up, all her diseases left her; and no sooner had all the girls taken him up in their arms than they too were cured of their afflictions by the blessing of Moses.

Then Āsiya took him, not knowing that he was the son of her uncle Amram, and carried him to Pharaoh, who said when he saw him, "Āsiya, I fear that this may be my enemy. I must therefore kill him."

"This child is a delight of the eye to me, and to thee," said Āsiya. "Kill him not, peradventure it may happen that he may be serviceable unto us; or we may adopt him for our son (28.9). Sire, if he be your enemy, you can have him destroyed whenever you wish. But keep him until such time."

As Moses was hungry, wet‑nurses were brought from every corner of the kingdom; but he would not take the breast of any of them, as He hath said: And we suffered him not to take the breasts of the nurses who were provided (28.12), lest he suckle at the breast of any but his mother.

Moses' mother longed to see him and said to her daughter, "Go seek news of your brother." When the girl came to the palace, which was not closed that day to women capable of nursing, she saw Moses on Āsiya's lap and said, "Shall I direct you unto some of his nation, who maV nurse him for you, and will be careful of him~" (28.12).

"Go and bring them to me," said Pharaoh.

She therefore returned to her mother and told her what hacl happened. Straightaway Jochebed, Moses' mother, went to Pharaoh .

"Take this boy," said Āsiya, "and I give him your breast. Per‑ [218] haps he will take it." She did as she was told, and Moses accepted her to nurse him. Jochebed lived three years in Pharaoh's house." (Thackston Kisa’I, 217-8)

The torture & Martyrdom of Āsiya

"Of striking similarity to Pharaoh's torture of Āsiya is the account of the martyrdom of St. Catherine: Asiya is tortured to death with iron stakes, after which the angels bear her off into heaven in a dome of light (see Nlsaburi, Qisas al‑anbiya', p. 187), a standard topos in martyrologies, cf. the old woman put to death by Nimrod (p. 141 above) and the martyrdom of Queen Alexandra in the St. George legend (Tha'labi, Qisas, p. 392 and also in the Syriac version in Acta martyrum et sanctorum, ed. Bedjan, I, 295ff.).

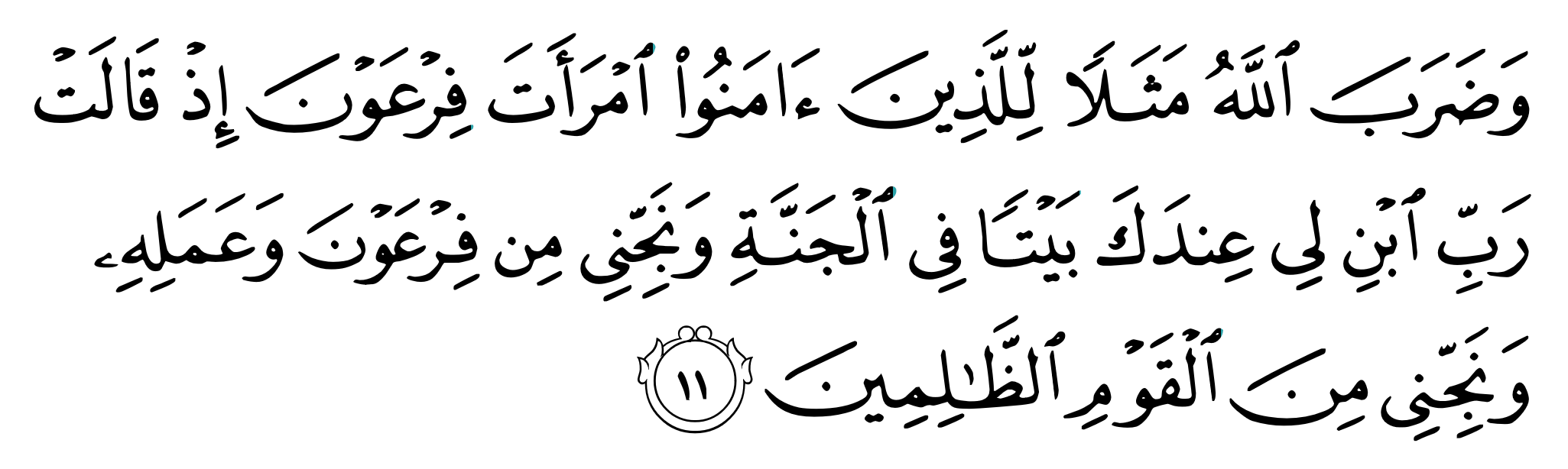

Qur’ān 66:11 and the last words of Āsiya in select Tafsir Literatures.

The final, last words of Āsiya are registered in Koran 66:11 as an example of true piety:

“And God sets forth an example of those who have believed: the wife of Pharaoh, when she said, "My Lord, build for me near Thee a house in Paradise (bayt an fi’l-jannat) and deliver me from Pharaoh (fir`awn) and his deeds and save me from the unjust people."

Qur’ān 66:11 in select Tafsir Literatures.

_________________

آسية بن الفرج الجرهميّة

The female contemporay of Muhammad Āsiya bint al-Faraj al-Jurumiyya = آسية بن الفرج الجرهميّة

The name and person of Āsiya in Baha’i sources

آسیه خانم

Āsiyah or Āsīyih Khanām wife of Bahā'u'llāh (c. 1820-1886) .

Āsiyah Khanām or Āsiyih Yalrúdí was the daughter of Mirza Ismáʼíl Yalrúdí of Mazandaran. She was married to Mīrzā Ḥusayn `Alī Nūrī, Bahā’u’llāh, in the year 1251/1835 when he was eighteen and she was around fifteen. Seven children named Kāzim; Sādiq; ʻAbbās; ʻAlí-Muhammad; Bahā’iyya; Mihdi and ʻAlí-Muhammad were born three of whom died in infancy. Āsiyah/Āsīyih was thus the mother of `Abbas Effendi, `Abdu'l-Bahā (1844-1921), Fātima Khanum entitled Bahā’iyya (1846 – 19XX) and Mīrzā Mihdi (born, Tehran ?1849) who died in Acre on June 23, 1870.

A new American Āsiya : Wallesca (Pollock) Dyar renamed آسية (Ar./Per. =) Āsiyyah or "Aseyeh" Allen.

In a scriptural Tablet dating to 1905 and probably addressed to the Bahā’ī writer Wallesca (Pollock) Dyar (renamed Aseyeh Allen), the wife of Harrison G. Dyar (d.1929), a somewhat heterodox or eccentric Bahā’ī,. `Abdu'l-Bahā states,

"That blessed name which thou hast asked to remain with thee forever and become the cause of spiritual progress -- that name is "Aseyeh," [ آسية = Āsiya] which is the name of the mother of `Abdu'l-Bahā. I give the blessed name to thee. Be therefore in the utmost joy and happiness, and be engaged in all gladness and attraction (or ecstasy) for thou hast become the object of such a favour." (TAB I: 209)

Perhaps in another scriptural Tablet or letter to the same American Bahā’ī, `Abdu'l-Bahā states that the use of the name آسية = Āsiya or "Aseyeh", "is acceptable in the Threshold of Oneness". This in that "the daughter of Pharoah had this name, who, when (Moses) the Light of Guidance dawned, became confirmed by the Merciful One, left the court of Pharoah with its grandeur and sovereignty, and became perfumed with the fragrances of holiness. Then she assisted in the service of His Holiness (Moses) -- upon her be peace!".

Following the above words `Abdu'l-Bahā adds that "Aseyeh was the name of my mother" (TAB I: 218). In this scriptural Tablet `Abdu'l-Baha assumes, following one thread of Islamic tradition and tafsir, that آسية , Āsiya was the name of a daughter of the Pharoah of Egypt (of uncertain identity) at the time of Moses who became a devout follower of Moses.

In 1920 Aseyeh Allen Dyar had published a volume entitled, Introduction to the Bahā’ī Revelation: Being a Series of Talks Given During the Summer of 1919 on a Trip through the Nothwest Introductory to a Statements of the Message of the Bahai Revelation. Washington, D.C., 1920. Her husband Harrison G. Dyar (d.1929) was an eccentric and somewhat heterodox American Bahā’ī. He at one time edited the now largely forgotten `Reality Magazine’ ( ) (see Smith). He wrote much on lepidoptera.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Al-Kisā’ī

Al-Tha`labī,

- X

- Trans Brinner