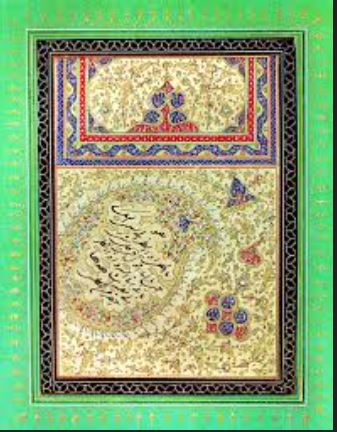

Bahā'-Allāh's later handwriting

An illuminated Scriptural Tablet of Baha'u'llah

The writings of Bahā'-Allāh (1817-1892 CE), An Introductory Note

Stephen N. Lambden

1985 - Now under revision and completion 2014

Bahā'-Allāh's extant writings very largely date from the last 40 years of his life (1852-1892 CE) and were written in Arabic and / or Persian, and sometimes a mixture of these languages. The Persian of Baha'-Allah is often highly Arabized. For the most part his writings are letters written in honor of and /or in reply to Bābīs and Bahā'īs and varying in length from a few lines to several hundred pages. Though largely untitled a proportion, perhaps 500 or more, usually of the more weighty, doctrinally significant writings, have specific designations. In line with the conviction that they were expressions of waḥy (divine revelation), the sacred kalimat Allāh (Word of God), like the (original) Torah, Gospels and Qur'ān, many of these writings have specific designations derived, for the most part, from time-honored (largely) Abrahamic religious terminology. Key designations for Baha'u'llah's writings thue include :

- (1) لوح , الواح Lawḥ (pl. alwāḥ), scriptural `tablets’. (Per.) Lawh-i aqdas (The Most Holy Tablet');

- (2) سورة / سور Sūrah, (pl. suwar). Surahs or (loosely), sections, `chapters'. Thus, for example, Surat al-Khitab ('The Surah of the Discourse'), Surat al-bayan (The Surah of the Exposition') ...

- (3) كِتَاب/ كُتُب Kitāb (pl. kutub), book, writings, letters, pages .. hence (Pers.) kitāb-i iqan (Book of Certitude) or (Arabic) al-kitab al-aqdas ("The Most Holy Book" = Per. Kitab-i aqdas).

- (4) صَحِيف / صُحُف Saḥīfa (pl. ṣuḥuf ) (scrolls, sacred writings'...), thus (Per.) Saḥīfa-yi Shattiyya (`The Scroll of the Torrent').

- (5) Risala (pl. Rasā'il), Treatise... e.g. (Per.) Risala su'al va jawab ('Trestise expressing Questions and Answers');

- (6) Tafsir (tafa'sir) or Sharh Commentary. e.g. Tafsir Surat al-shams (Commentary on the Surah of the Sun = Q. 91).

- (7) Ziyarat-Nama (Visitation Tablets). e.g. (Per.) Ziyarat-nama-yi Tahira, Qurrat al-`Ayn (Visiting Tablet for Tahira [Fatima Baraghani, d. 1852 CE.], the `Solace of the Eyes')

- Add

(1) Lawḥ (pl. alwāḥ), Tablet.

The Qur'anic Arabic word for scriprural Tablet is Lawḥ (pl. alwāḥ) which corresponds to the biblical Hebrew ל֥וּחַ = luḥ (pl. luḥōṯ = הַלֻּחֹ֥ת = "the Tablets" ). This biblical term indicates, among other things, the חָר֖וּת עַל־ הַלֻּחֹֽת׃ , Tarot `al ha-luḥōṯ = " the Tablets of the Law (Torah)" given by God (on Mt. Sinai) to the prophet Moses (Exodus 32:16). The phrase הַלֻּחֹ֥ת ha-luḥōṯ, "The Tablets", occurs some 14 times in the Hebrew Bible largely in connection with the "Tablets of the Law" (see also, Exodus 32:19; 34:1, 28; Deut. 9:17; 10:2ff., etc.).

In the Qur'an the Arabic masculine noun lawḥ ("Tablet") or its plural alwāḥ occur five times. Three of these occurences are of the plural الواح alwāḥ and are found in the 7th Surat al-A’rāf ("the Heights"). They relate to the episode of Moses' receipt of the `Tablets of the [Israelite, Jewish] Law' on Mount Sinai and his subsequent destruction of them when he observed what Aaron and the people has done (see Q. 7:145,150,154):

Q. 7:145.

"And We ordained laws For him [Moses] in the Tablets (alwāḥ). In all matters, both Commanding and explaining All things (kulli shay' in), (and said): "Take and hold these With firmness, and enjoin Thy people to hold fast By the best in the precepts: Soon shall I show you The homes of the wicked,— (How they lie desolate)."

Q. 7:150.

"When Moses came back To his people [from Sinai], angry and grieved, He said: "Evil it is that ye Have done in my place In my absence: did ye Make haste to bring on The judgment of your Lord?" He put down the Tablets (al-alwah), Seized his brother by (the hair Of) his head, and dragged him To him. Aaron said: "Son of my mother! The people Did indeed reckon me As naught, and went near To slaying me! Make not The enemies rejoice over My misfortune, nor count thou Me amongst the people Of sin."

Q. 7:154.

"When the anger of Moses Was appeased, he took up The Tablets (alwāḥ) : in the writing Thereon was Guidance and Mercy For such as fear their Lord".

The fourth Qur'anic reference is connected with the story of Noah and his Ark found in Surah 54, the Surat al-Qamar (Surah of the Moon). The ark which bore Noah is referred to as a "well-planked vessel, well-cauked" (so Arberry trans.) This illustrates the sense of Lawḥ (pl. alwāḥ) as a wooden plank, also suggestive of a flat surface which something might be written upon as is the case with inscribed scriptural "Tablets".

Q. 54:13.

![]()

"But We bore him [Noah] on an (Ark) made of Broad planks ( dhat alwāḥ) and caulked With palm-fibre (dusur in)"

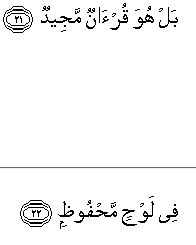

The fifth and final Qur'anic reference to a (sing.) lawḥ is found in the eighty-fifth Surat al-Burūj, (The Surah of the Zodiacal Signs) :

Q. 85: [21-]22.

"Nay! Such is a Glorious Qur'an (Qur'an majid) [85] [inscribed] in a Preserved Tablet (Lawḥ in Mahfuz in)".

Here reference is made to the well-known "Guarded Tablet" (Lawḥ Mahfuz) about which a great deal has been written by Muslim Qur'an commentators as well as by the early Shaykhi leaders - Shaykh Ahmad al-Ahsa'i (d.1241/1826) and Sayyid Kazim al-Rashti (d. 1259/1843). Soo too both the Bab and Baha'-Allah.

Individual items of sacred writ deriving from Baha'-Allah are very often referred to as "Tablets" whether they be in Persian or Arabic (or both), very brief or very long; whether relating to matters "mundane" or to matters profoundly theological or to issues of global significance. Many writings are generally called `Tablets' despite the fact that they may have other names or deisignations such as are listed above. Thus, in other words, on occasion, the totality of Baha'i scriptural writings are reckoned alwāḥ (`sacred Tablets') as are writings also given other literary designations such as those discussed here, e.g. Surahs, Books, Treatises, Scrolls, etc.

(2) Sūrah, (pl. suwar).

(3) Kitāb (pl. kutub), "Book", "Letter" ...

The word Kitab in Arabic indicates a letter, book or written composition of some kind. A farly large numnber of Baha'-Allah's writings are designated books (kitab, pl. kutub). A well-known example would be the Kitab-i iqan or Book of Ceritude which dates to around 1862. From the Edirne or Adrianope period a weighty, over 200 page volume is his Kitab-i badi` (The Revolutionary or Wondroud Book). Books from the later West Galilean or (loosely designated) `Akka' period include his centrally important book of laws and injunctions designated in Arabic al-kitab al-aqdas ("The Most Sacred Book") which is often (loosely) rendered into Persian as Kitab-i aqdas. (c. 1873). Among the fairly short works of designated books is the late al-Kitab al-`Ahdi (The Book of My Covenant) again loosely rendered into Persian as the Kitab-i `ahd ("The Book of the Covenant").

4) Saḥīfa (pl. ṣuḥuf ).

Occurring eight times in the Qur'an (=Q.), the originally Sabaic word ṣaḥīfa (pl. ṣuḥuf) may have originally meant something like `document'. According to Arabic sources this word indicates a `sheet’ or piece of material for writing upon; hence, `document' , `page of writing’, `scroll’, `scripture’, etc (Jeffery, 1938:192-4; Ghédira, `ṣuḥuf’', EI2 VIII: 834-5; Maraqten, 1998:309). Though the Q. says very little about divine revelations sent down prior to the time of Moses, the word ṣuḥuf ("scriptures") is used in this connection. There is mention of the "earlier scriptures" (al-ṣuḥuf al-ulā), the ṣuḥuf Ibrahīm wa mūsā ("The Scriptures of Abraham and Moses" Q. 87:19).

In one way or another the Arabic words ṣaḥīfa and ṣuḥuf are quite common in Bābī-Bahā'ī sacred literatures, often indicating specific revealed writings as well as indicating pre-Islamic or especially pre-Mosaic divine revelation. Both the Bāb and Bahā'-Allāh used ṣaḥīfa in varied and diverse ways to indicate portions of their sacred writings. The Bāb, for example, wrote a Ṣaḥīfa bayn al-ḥaramayn usually loosely rendered `Epistle between the Two Shrines' [Mecca and Medina], (Muḥarram 1261/ mid.Jan. 1845) and Bahā'-Allāh authored the Ṣaḥīfa-yi Shaṭṭiyya (Scroll of the Raging Torrent, c.1857-8) as well as a Ṣaḥīfat Allah ("The Scroll of God", c. 1858) perhaps 25 or more years later (from or near Acre in Ottoman Palestine) addressed especially to a group of Iranian Jewish converts to the Baha'i religion.

(5) Risala (pl. Rasa'il), Treatise...

Risala (Treatise)

(e) risāla [-yi] ----- ) treatises

(6) Tafsir (tafa'sir) or Sharh Commentary.

An Islamic Tafsir writing is a commentary or work expository of portions or of the whole of the Qur'an though thuis work may be indicative of the attempt to explain some other weighty composition.

(f) tafsīr-i ----- ( commentaries).

Tafsīr-i - ( Commenty on ).

Sharh-i (Commentary on).

(7) Ziyarat-Nama (Visitation Tablets)...

Ziyarat-Nama (Visitation Tablets) as texts of varying lengh in Persian or Arabic (or both) which commenorate a deceased individual and is meant to be recited at his or her resting place. There are scores of Ziyara texts of importance in Shi`i Islam especially those centered upon the twelver imams, from `Ali ibn Abi Talib (d. 40/661) to Imam Muhammad al-Mahdi (d. 260/8XX), the twelfth Imam who is thought to be in the heavenly world in occultation (al-ghayba). There are Shi`i Islamic visitation texts for the Prophet Muhamad himself, his daughter Fatima and his descendants the twelve Imam. Some important Ziyara texts suffice for one or more of these Islamic worthies.

Very few of the the sacred `revelatory' (Ar. w-h-y) writings of Baha'-Allah indicated above, are studied or systematic compositions. Perhaps In excess of 500 works of Bahā'-Allāh were specifically titled by their author after terms or themes of central importance therein. Others are named or titled after the recipient (s) of the scriptural writing. Some writings have several titles or names such as the Lawḥ-i kāf-zā' (`Tablet of K and Ẓ', alluding the his major disciple Kāẓim Samandar who is honored therein) though this text is also known as the Lawḥ-i Fu`ād Pashā, the one-time Turkish Foreign Minister named Keçecizade Mehmed Fu'ād Pashā (1814-1869 CE) who is once directly addressed therein.

Only a small proportion of Bahā'-Allāh's "revelations" were written down by Bahā'-Allāh himself; largely revelations dating before the mid-1860s. The vast majority of them were rapidly dictated to amanuenses and subsequently `transcribed', neatly written for distribution and often checked by their author. [1] A proportion of the alwaḥ (Tablets) of Baha'u'llah contain sometimes abrupt changes of language, form, style and/or content and exhibit grammatical peculiarities. [2] Some were written as if by the Bāb or leading Bābīs, most notably Mīrzā Āqā Jān of Kāshān, Mirza Khadim-Allāh (`The Servant of God' d.190X) Bahā'-Allāh's leading amanuensis. [3]

Between 1852 and 1892 Bahā'-Allāh wrote or dictated something like 10,000 - 20,000 items of sacred scripture. There writings include a large numbers of Arabic and Persian poetical compositions, large quantities of prayers, meditations and various kinds of devotional texts including celebratory ziyarāt-namih compositions (commemoratory, `Visiting tablets') as well as Dhikr-type litanies, mystical revelations, visionary narratives, allegorical prophecies, ritual and legalistic directives and ethical exhortations. They include, furthermore, theophanological proclamations and commentaries upon biblical, qur'ānic and other sacred texts and religious traditions.

Apart from thousands of letters to communities, groups and individual Bābīs and Bahā'īs, Bahā'ī scripture includes a fairly large number of epistles addressed to Jews, Christians, Zoroastrians, Sunnī or Shī`ī and Shaykhī Muslims, Azalī Bābīs, diverse oriental rulers, diplomats and freethinkers and a number of Western monarchs and leaders. [1] By the time of his residence in Edirne (1863-8) Bahā'-Allāh claimed to have revealed the equivalent of all that God had communicated to past prophets and Messengers. Towards the end of his life he estimated that his collected revelations would fill 100 volumes (Lawḥ-i Shaykh, XX ETr. ESW:115, 165 cf. GPB:xxx ).

The present writer is aware of about 35 major titled writings dating from the Iraq period (1853-1863), 50 or more from the Istanbul-Edirne period (1863-1868) and 100 or more dating to the years in Ottoman Palestinian, the West Galilean or (loosely) Acre (=`Akkā') period (1868-1892). Bahā'-Allāh did not keep a complete, centralized collection of his writings or arrange for such a collection to be made during his lifetime, though many important sometimes large manuscript collections were made before (and of course) after his passing in 1892 CE. In his Persian Lawḥ-i Sarrāj [Siraj] (c. 1867) he explicitly states that he did not desire any systematic collection and circulation of volumes of his writings as this could only be befittingly accomplished in the future (Lawḥ-i Sarrāj, 91 cf. RB2:269).

Up till now, by no means all of Bahā'-Allāh's writings have been collected together, classified, collated or studied by researchers working at the Bahā'ī world center in Haifa (Israel) or other scholarly individuals or institutions Only a small proportion of these writings (largely major titled alwaḥ ) have been published in the original languages and even fewer translated into English (or other languages). [3] Much research will need to be carried out before the Sitz-im-leben ('Setting in Life', context) and hence the specific meaning of a good many writings becomes clear. The exact or even general dating of certain major and many minor revelations remains uncertain. Only a limited number of alwaḥ are dated; most notably revelations as if by the aforementioned Mīrzā Āgā Jān of the mid-late West Galilean (Acre) period. Some works of Baha'u'llah are of doubtful authenticity or contain faulty insertions or interpolations. Others exist in several evolving recensions all "sound" expressions of the revelation of their author (e.g. Rashh-i `ama' 1852/60s/ etc and Surat al-haykal, 1867-8+73?). Critical editions of Bahā'ī scripture remain a thing of the future as does the befitting scholarly publication of autograph and scholarly editions.

Bahā'-Allāh used at least ten variously inscribed seals arranged in one diagram rather like one of the major Jewish mystical portrayals of the Sefirot or Divine "emanations" (see the plate facing p.78 of Taherzadeh's Revelation of Baha'u'llah vol. 1). He did not, however, seal all his revelations and writings falsely attributed exist. Printed scientific critical editions of Bābī and Bahā'ī scripture are largely a thing of the future. Currently published editions of Bahā'-Allāh's writings (or those printed in compilations) are by no means always based on autograph or reliable mss. In certain printed volumes, including Ishrāq Khāvarī's 9 volume Ma'idih yi āsmānī ("The Heavenly Table"), errors are legion, especially in Arabic alwāḥ copied by Persians and others without an adequate knowledge of Bābī-Bahā'ī scriptural Arabic, an admittedly complicated body of religious literature.

The exact person or multiple persons to whom many scriptural writings or (collectively) alwah were addressed, remains uncertain or unknown. This in part due to Bahā'-Allāh's extensive use of alphabetic and other ciphers (largely for security reasons) and the fact that many of the individuals addressed bore the same name(s). All in all the scholarly study of Bahā'-Allāh's writings has hardly begun. Many fascinating discoveries await the patient researcher of Bābi-Bahā'ī doctrine and history.